This is the third briefing in a study that investigated public attitudes to labour migrants in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data presented here were collected in January 2021.

-

Key Points

- Public attitudes towards migrant workers were most favourable in London and Scotland and least favourable in the North East.

More… - The longer migrant workers were in the UK, the more public appetite there was to grant them access to welfare benefits, with little variation in support across the UK.

More… - Whether or not a migrant works a job considered essential to the UK’s COVID-19 recovery was an important criterion when considering their priority for admission and economic contribution in all areas of the UK, but especially in the East of England and the South West.

More… - Migrant workers’ skill level affected public attitudes towards them in all parts of the UK – although most in Yorkshire and the Humber and the West Midlands, and least in London and the South East.

More… - Across the UK, ‘essentialness’ influenced public opinion towards migrant workers about as much as skill level.

More… - Nationality was less of a factor in determining public preferences to migrants than skill level and essentialness, although more negative views towards Chinese migrants were evident in many areas.

More…

- Public attitudes towards migrant workers were most favourable in London and Scotland and least favourable in the North East.

-

Understanding the Evidence

The data used in this briefing come from the first wave of a three-wave online panel survey. ... Click to read more.These data were collected by YouGov in January 2021 under the project Tracking Public Attitudes and Preferences for Post-COVID-19 Labour Migration Policies, which aimed to better understand public attitudes towards migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

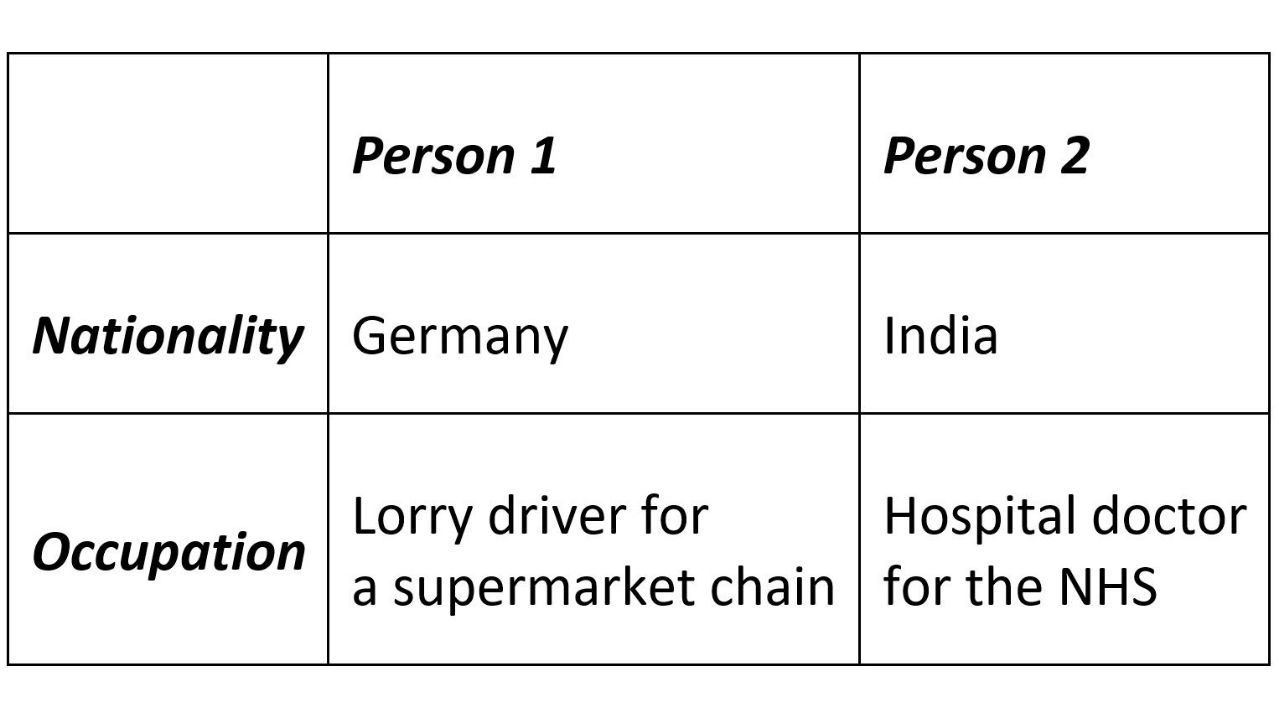

The survey was composed of two sections. The first asked respondents about how their employment status and income changed during the pandemic. The second presented respondents with pairs of hypothetical migrant ‘profiles’ that varied in their nationality and occupation, such as:

Respondents were then asked to rate each of these persons in terms of:

- Preference for admission to the UK

- Benefit to the UK economy

- Access to different types of benefits upon arrival to the UK

- Access to different types of benefits after five yours of living in the UK

This briefing adds a geographical element to two previous publications coming out of the project. The first looked at the UK public’s preferences around the admission of different types of migrant workers and their perceived benefit to the UK economy (points one and two, above). The second looked at how willing the public was to extend benefits to different types of migrant workers (points three and four, above). Please refer to the Understanding the Evidence sections in those briefings for more detailed information about the survey methodology and the questions posed to respondents.

There are some important caveats to consider when shifting the analytical lens from survey data on the UK as a whole to smaller geographical areas (and therefore smaller population groups). In the first instance, the smaller the sample size, the less confident we are in the results. For this reason, the analysis below is based on data from the first wave of the survey, as it has the largest sample of the three waves. This also explains why we were unable to provide information below national and regional levels.

Note also that while at the UK level the survey is designed to be representative of the population in terms of most socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, education, gender and EU referendum vote, this is not necessarily the case at the national and regional levels (although the sample is representative in certain respects, such as the 2019 general election vote – for more information, see YouGov’s Panel Methodology webpage).

During the analysis, we applied weights to better understand whether there was a significant bias in the sample at national and regional levels in terms of age, gender and education. Overall, we found that the pre-weighted findings held – that is, there was not a significant bias at national and regional levels. Our suspicion is this is primarily due to the stratified sampling at the UK level and the likelihood that characteristics such as age and education track the 2019 general election vote, which is stratified within UK nations and regions. As we did not find responses significantly biased below the UK level, this briefing reports on the actual responses of those interviewed (rather than using our post-stratification weights). All findings discussed in the text are statistically significant.

-

Understanding the Policy

The UK’s immigration system is one element of government policy influencing – and potentially being influenced by – public attitudes towards immigration (e.g., Dempster and Hargrave, 2017). ... Click to read more.Following the UK’s departure from the EU and the end of Free Movement, most migrants wishing to come to the UK for the purpose of work must be in jobs with a skill-level of at least medium-high, whether or not their job is considered essential to the COVID-19 recovery or otherwise in the public interest. Skill level is classified according to the Government’s Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF). The RQF bases its classification on the amount of training an occupation typically demands: occupations requiring short-term or on-the-job training are usually classed as low skilled; those requiring more significant (e.g., vocational) training – middle skilled; and those requiring university degrees – high skilled. The UK’s immigration policy is decided centrally and, on the whole, applies equally in all nations of the UK, although this does not mean public attitudes towards immigration and immigrants across the UK are uniform (for more detail see Location, Location, Location: Should Different Parts of the UK Have Different Immigration Policies?).

Integration policy, which aims to mediate the processes through which migrants and longer-standing residents participate in society, plays an role in shaping people’s experiences of migration and relationship to migrants in their local communities, as well as their attitudes towards migration in general (Strang and Ager, 2010). It is, broadly speaking, a devolved matter and whilst there is no UK-wide integration strategy concerning migrants, there are strategies in the devolved administrations. Integration programming ranges from English language classes to housing services, from community festivals to job training schemes for refugees. They are formulated and carried out in various departments at all levels of government and by non-governmental actors; see, for example, Making connections, building resilience: the Yorkshire and Humber refugee integration strategy. For more information about integration policy in the UK, see Policy Primer: Integration.

Likewise, the resources, policies and programmes leveraged to combat the COVID-19 pandemic differed across the UK and the impact – social and economic – of the pandemic has been experienced differently in different parts of the UK. This is thought to have contributed to public opinion on a variety of issues, such as immigration (Lalot et al., 2021). For examples of local response, see Inclusive Cities: Integration policy and practice during COVID-19, which captures the inclusion work of 12 Local Authorities from across the UK during the pandemic.

London and Scotland were the most positive towards migrant workers and the North East was the most negative.

When asked to rate migrant workers on a 1-7 point scale according to a) priority for admission to the UK and b) their potential contribution to the UK economy, the UK public gave average scores of 4.6 and 4.7 respectively (Figure 1). There was little variation in attitudes between different parts of the UK, although some differences were notable: respondents from London and Scotland held more positive views on migrant workers’ admission to the UK and contribution to the UK economy than elsewhere, while the North East was the most negative on both counts.

These small differences are broadly in line with existing public attitudes research (e.g., Migration Observatory, 2011; Murray and Smart, 2017; Crawley et al., 2013). They can largely be explained by the composition of the respective local populations, and the ways in which it affects public opinion: young and highly educated residents, such as those more typically found in London, are expected to hold more positive opinions towards immigration compared to their older, less educated peers, who are on average more likely to live in the North East (ONS, 2020; Kunovich, 2004)Similarly, attitudes are more positive in terms of admission and economic contribution in urban than rural areas. These differences are also reflected in voting patterns, for example in the UK’s referendum to leave the EU (Goodwin and Heath, 2016). The more positive attitudes found in Scotland are typically attributed to several interlinked factors, such as conversations around independence and a self-determined immigration policy, the Scottish Government’s own strategies to attract and retain non-UK nationals, and the significant role of international migration in the nation’s population growth (Scottish Government, 2019; McCollum et al, 2013; Migration Observatory, 2013 and 2014).

Figure 1

The longer a migrant worker stayed in the UK, the more the public supported their access to welfare benefits in all areas of the UK.

After spending five years in the UK, migrant workers enjoyed greater public support for their access to housing benefits, NHS primary care and Universal Credit, than upon arrival. London and Scotland were the most positive both after five years as well as upon arrival. On the whole, the North East was the least positive.

Figure 2

People living in the East of England, the South West and Wales all placed high premiums on migrants who work in essential jobs, whereas ‘essentialness’ mattered less in London and the North East.

When it came to prioritising admission to the UK, there was a premium given to migrants working essential jobs compared to those in non-essential jobs in all UK nations and regions (Figure 3). Nowhere was this premium greater than in the East of England, the South West and Wales, all of which ranked workers in essential jobs relatively high and those in non-essential jobs relatively low. Essentialness mattered least in terms of admission priority in London and the North East, although for different reasons. London had the most positive attitudes in the UK towards the admission of workers in both essential and non-essential occupations, in effect shrinking the premium given to those in essential jobs, whereas in the North East this gap narrowed because it was the least positive area in terms of the admission of migrant workers in both essential and non-essential occupations.

Views on the economic contribution of workers in essential and non-essential occupations followed the same trends as priority for admission. They were, however, more measured than when considering admission, with slightly smaller premiums given to essentialness across the UK.

The fact that information about the migrants’ occupations mattered less to respondents in London and the North East – where overall attitudes were the most and least positive, respectively – supports the view that those ‘in the middle’ of the immigration debate are more nuanced and flexible in their evaluations of immigrants than those at either extreme (Rutter and Carter, 2018).

Figure 3

When considering admission to the UK, the skill level of migrant workers mattered most to residents of Yorkshire and the Humber and least to Londoners – this skill premium was less evident when considering migrants’ economic contribution.

Migrants in occupations classified as high-skilled were prioritised for admission to the UK by respondents in all parts of the UK over migrants in low-skilled occupations (Figure 4). This is consistent with the Government’s post-Brexit immigration policy which is orientated towards the admission of migrants working in high- (and medium-) skilled occupations. The premium afforded to workers in higher skilled occupations, which was particularly pronounced in Yorkshire and the Humber, was relatively muted in London, which gave workers in both high- and low-skilled occupations the highest rankings for admission to the UK of any UK nation or English region.

Most parts of the UK were slightly more positive about the potential economic contributions of migrants in high-skilled jobs, and slightly less negative towards those in low-skilled jobs, resulting in lower skill premiums than was the case when considering admission priority.

For information about how occupational skill-level is classified, see the Understanding the Policy section, above, and earlier briefings from this project.

Figure 4

Skill-level mattered slightly more than essentialness for people in most areas of the UK when considering migrants’ priority for admission to the UK and their potential contribution to the UK economy.

In most parts of the UK, migrants working in high-skilled occupations were rated about the same as or slightly more favourably for admission to the UK than those working in occupations classified as essential to the UK’s COVID-19 response (Figure 5). This favourability gap was greatest in the North of England and lowest in the South East, Wales and the South West – the only three areas of the UK where workers in essential occupations were rated roughly the same or slightly higher than those in high-skilled occupations. The picture was broadly similar when respondents were asked to consider migrants’ contribution to the UK economy, with slightly higher premiums given to workers in high-skilled occupations than essential occupations.

At the same time, most areas of the UK rated workers in low-skilled jobs about the same as, or slightly worse than, workers in non-essential jobs when considering both admission and economic contribution. As with the ratings of migrants in high-skilled and essential occupations, valuations of migrants working in low-skilled and non-essential occupations diverged more in the north of England, whereas in the south of England and Wales there was little to no difference.

Looking to the small absolute differences, however, these figures can also be interpreted to show broad agreement amongst residents of the different areas of the UK.

Figure 5

Although nationality was not as important a driver of attitudes as essentialness or skill-level, in nearly all parts of the UK, Chinese migrant workers were among the most heavily penalised of nationalities when considering admission and economic contribution

Previous research found that Chinese minorities in the UK were not the most discriminated against (Heath & Di Stasio, 2019). Contrary to this, our survey found Chinese migrants were either the most or second-most heavily penalised nationality in terms of consideration for admission to the UK in most parts of the UK among the 10 nationalities we asked about. Evaluations were most negative in the North East and Northern Ireland, while in the East of England, Scotland and Yorkshire and the Humber they were not statistically distinct from attitudes towards Australians, who received the highest rankings in all parts of the UK (Figure 6).

A similar picture emerged when considering migrant workers’ potential economic contribution. Chinese nationals were again penalised in comparison to Australians – particularly strongly in the North East, Northern Ireland and the South East. Only in Scotland and Yorkshire and Humber was no penalty observed.

Considering the UK as a whole, respondents’ respective preferences towards Australian and Chinese nationals remained consistent later on in the pandemic. For analysis of subsequent waves of the survey upon which this briefing is based, see Public attitudes to labour migrants in the pandemic: dynamics during 2021.

Figure 6

Acknowledgements

This briefing was produced with support from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) funding through its ‘Ideas to Address COVID-19’ scheme. Thanks to Pip Tyler for her comments on a previous draft of this briefing.

References

- Crawley, H., S. Drinkwater and R. Kauser (2013) Regional Variations in Attitudes Towards Refugees: Evidence from Great Britain. Available online.

- Dempster, H. and K. Hargrave (2017) Understanding public attitudes towards refugees and migrants. ODI Working Paper 512. Available online.

- Goodwin, M.J. and O. Heath (2016) The 2016 Referendum, Brexit and the Left Behind: An Aggregate-level Analysis of the Result. The Political Quarterly, 87(3): 323-332.

- Heath, A. F. and V. Di Stasio (2019). Racial discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: a meta‐analysis of field experiments on racial discrimination in the British labour market. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(5): 1774–1798. Available online.

- Kunovich, R.M. (2004) Social structural position and prejudice: an exploration of cross-national differences in regression slopes, Social Science Research, 33(1): 20-44.

- Lalot, F., D. Abrams, J. Broadwood, K.D. Haydon and I. Platts-Dunn (2021) The social cohesion investment: Communities that invested in integration programmes are showing greater social cohesion in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology: 1-19. Available online.

- McCollum, D., A. Findlay, D. Bell & J. Bijak (2013) Patterns and perceptions of migration, is Scotland distinct from the rest of the UK?” CPC Briefing Paper 10, ESRC Centre for Population Change, Southampton.

- Murray, C. and S. Smart (2017) Regionalising Migration: The North East as a Case Study. IPPR. Available online.

- Migration Observatory (2013) Bordering on confusion: International migration and implications for Scottish independence. Available online.

- Migration Observatory (2014) Scottish Public Opinion. Available online.

- Migration Observatory (2011) UK Public Opinion toward Migration: Determinants of Attitudes. Available online.

- ONS (2020) Living longer: trends in subnational ageing across the UK. Available online.

- Scottish Government (2019) Protecting Scotland’s Future: The Government’s Programme for Scotland 2019-20. Available online.

- Strang, A. and A. Ager (2010) Refugee Integration: Emerging Trends and Remaining Agendas. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23(4): 589-607.