This is the fourth briefing of a study that investigated public attitudes to labour migrants in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on tracking preferences over time. The data presented here were collected during January and June-July 2021.

-

Key Points

- While attitudes towards migrants vary substantially depending on migrants’ characteristics, growing evidence suggests that public opinion about immigration may be more stable in the face of shocks than previously thought.

More… - Although public attitudes continued to be more positive towards migrants in jobs considered essential during the pandemic by the UK Government, this positivity lessened between January and June-July 2021 with respect to admitting migrants working in essential occupations.

More… - Attitudes towards migrants working in higher-skilled occupations remained more positive compared to lower-skilled occupations, but the gap between these groups narrowed.

More… - Among the 10 nationalities considered in the study, public attitudes continued to be least positive towards migrants from China and most positive towards Australian migrants, although migrants’ occupational essentialness and skill levels generally mattered more.

More… - Public preferences remained highest towards granting primary healthcare access to migrants (as opposed to Universal Credit or Housing Credit) regardless of how long they had been in the country. However, public willingness decreased between January and June-July 2021 when considering migrants who had lived in the country for at least 5 years, especially for those working in essential occupations.

More…

- While attitudes towards migrants vary substantially depending on migrants’ characteristics, growing evidence suggests that public opinion about immigration may be more stable in the face of shocks than previously thought.

-

Understanding the Evidence

The overall objective of the project is to understand (1) what determines public attitudes towards migrant labour and migration policies during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) whether these attitudes are dependent on migrants’ occupation, which vary in terms of occupational skill levels and essentialness to the COVID-19 response, (3) whether attitudes vary across UK regions, and (4) the longevity of any observed attitudinal shifts, particularly in relation to the government’s efforts at developing and implementing policies for economic recovery.... Click to read more.The data presented in this briefing comes from two waves of a survey fielded by YouGov UK in January and June-July 2021 to a nationally representative sample from an online panel (YouGov 2021). Here, we focus on reporting on the dynamics of aggregate-level attitude change. The January wave comprised 4,954 adults living in the UK, while the June-July wave comprised 3,261 respondents from the January wave who were successfully recontacted (representing a recontact rate of about 66%). Longitudinal studies like this one enable researchers to measure the extent to which attitudes and preferences change or remain stable during this key period—something that single surveys (as ‘snapshots’ in time) cannot reveal.

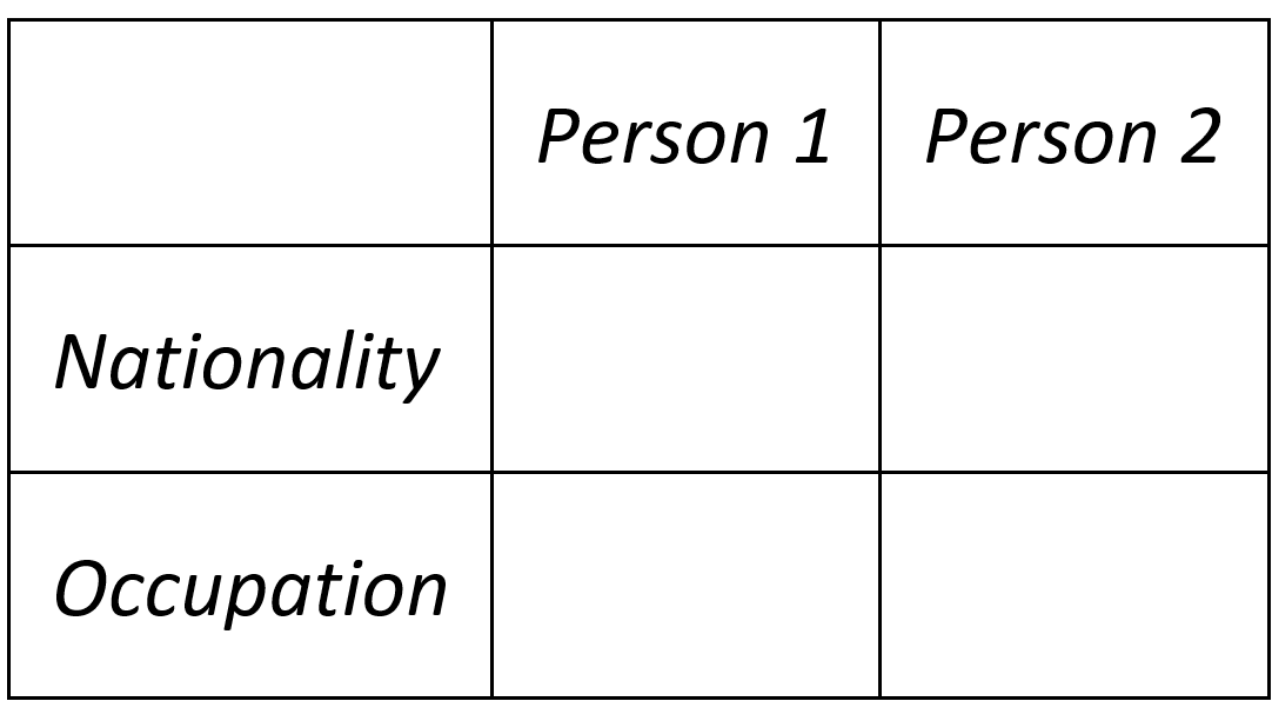

The part of the survey on which this briefing is based presented respondents with pairs of hypothetical migrants‘ profiles. The only information that was given about these profiles was their nationality and occupation:

Here are the profiles of two people who could apply to enter the UK.

Respondents were asked to rate their preference for admitting each person to the UK, their perception of how much each person contributes to the UK economy, and their support for each person’s right to access the following three benefits upon arrival and after five years of residence in the UK: Universal Credit (payment to help with living costs), Housing Assistance (financial help for housing from the local council) and National Health Service Primary Care (first point of contact for healthcare, usually a general practitioner).

Each respondent evaluated three pairs of profiles in total. We considered 12 occupations and 10 nationalities, which were randomly assigned to the profiles presented to respondents. The nationalities reflect some of the top countries of origin of migrants in the UK, key population groups in the public debate and are geographically and ethnically diverse (Australia, China, Germany, India, Italy, Jamaica, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, and Romania). The occupations have a substantial share of migrant workers and vary with regard to skill level—along the lines of low and medium-low skilled vs high and medium-high skilled, based on ONS (2010) categorisation—and essentialness, as indicated by their inclusion or exclusion from the UK government’s list of essential workers during the pandemic (Office for National Statistics 2020).

Methodological note about conjoint analysis

Conjoint analysis is a survey experimental technique that estimates respondents’ preferences given their overall evaluations of alternative profiles that vary across multiple attributes. Usually, researchers are interested in estimating how different values of an attribute – for example, nationality or occupation – influence the probability of choosing a given profile or rating a profile with a specific score. One advantage of conjoint survey designs is that respondents do not have to see all possible unique profiles (in this study, the total number of unique nationality-occupation combinations is 120). Another advantage is that it can reduce social desirability bias on sensitive topics like migration (see Creighton and Jamal 2022) by allowing respondents to justify their responses along any of the criteria. Therefore, conjoint experiments are efficient at revealing respondents’ preferences that may have multiple dimensions. For more information about conjoint analysis, see Hainmueller et al. (2014).

While attitudes towards migrants vary substantially depending on migrants’ characteristics, growing evidence suggests that public opinion about immigration may be more stable in the face of shocks than previously thought.

A great deal of research shows how public opinion about immigrants depends on which types of migrants are involved (see the Migration Observatory briefing, Who Counts as a Migrant? Definitions and their Consequences). Moreover, external events, migratory flows, media coverage, and political settings also likely matter for attitude formation.

However, evidence across many immigrant-receiving countries also suggests that public opinion may be more stable in the longer-run: despite short-term shifts in public concern about immigration—perhaps in response to crises or political developments—these tend to wear off as time goes on (Claassen and McLaren 2021). Therefore, rather than expecting immigration attitudes to dramatically and permanently change as a result of significant shocks, it is more likely that attitudes remain relatively stable despite these events (Kustov, Laaker, and Reller 2021). The results shown in this briefing, taken at two different time points in the UK’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, lend support towards this conclusion.

Although public attitudes continued to be more positive towards migrants in jobs considered essential during the pandemic by the UK Government, this positivity lessened between January and June-July 2021 with respect to admitting migrants working in essential occupations.

In January 2021, the UK was entering a third lockdown. At this time, the UK public expressed more favourable attitudes towards migrants working in jobs considered essential by the government (Office for National Statistics 2020). These kinds of migrants were more likely to be preferred for admission into the UK, and were perceived to have a more positive impact on the UK economy. ‘Essential’ occupations in our study included doctors, care workers, secondary school teachers, supermarket lorry drivers, pharmaceutical lab technicians, and meatpackers.

This pattern continued into June-July 2021 (Figure 1), when restrictions had been largely lifted (though some variations still existed in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland). At this point in time, respondents still preferred admitting workers in essential occupations over non-essential occupations by 0.44 on a 7-point scale. However, this preference for essential workers was lower than in January, when respondents preferred admitting essential workers by 0.56 on a 7-point scale. (Throughout this briefing, any highlighted differences are statistically significant). Respondents evaluated the economic impact of essential workers more favourably than non-essential workers, a view that did not change significantly between January and June-July 2021.

Attitudes towards the 12 specific occupations in the study largely remained similar both in scale and rank order (Figure 1). Doctors were most preferred, while warehouse workers in non-essential sectors were least preferred. Despite recent concerns about truck drivers and supply chains, this was apparently not salient for public attitudes at the time of the survey fieldwork in June-July, as responses towards this occupation did not significantly change in either direction from January. Although respondents did express significantly higher admission preferences for waiters in restaurants—possibly explained by well-publicised shortages in the hospitality sector as the industry began re-opening—this did not reflect a substantial shift.

Figure 1

Attitudes towards migrants working in higher-skilled occupations remained more positive compared to lower-skilled occupations, but the gap between these groups narrowed.

Throughout the first half of 2021, the UK public continued to express more willingness to admit migrants working in high or medium-high skilled jobs, and viewed these people as having a more positive impact on the UK economy, compared to those working in low or medium-low skilled jobs (Figure 2). However, similar to migrants working in essential jobs, this gap narrowed between January and June-July: on the likelihood of admission, from 0.69 to 0.57 on a 7-point scale, and from 0.66 to 0.55 on the same scale when considering economic perceptions.

Figure 2

Among the 10 nationalities considered in the study, public attitudes continued to be least positive towards migrants from China and most positive towards Australian migrants, although migrants’ occupational essentialness and skill levels generally mattered more.

In January 2021, the UK public viewed migrants from China most negatively: they were least likely to be preferred for admission and were viewed as having the least positive impact on the UK economy compared to other nationalities. This pattern was consistent through to June-July (Figure 3). By contrast, migrants from Australia, Germany, and Italy remained more positively viewed. However, looking at the magnitude of these differences, essentialness and occupational skill appear to matter more than national origins when it comes to the UK public’s willingness to admit migrants and its perceptions of migrants’ economic impacts.

Figure 3

Public preferences remained highest towards granting primary healthcare access to migrants (as opposed to Universal Credit or Housing Credit) regardless of how long they had been in the country. However, public willingness decreased between January and June-July 2021 when considering migrants who had lived in the country for at least 5 years, especially for those working in essential occupations.

In January 2021, the UK public was more willing to extend access to primary healthcare (e.g., NHS general practitioners) to migrants who had just arrived compared to other welfare benefits such as Universal Credit or Housing Assistance—and particularly for migrants working in essential occupations compared to non-essential occupations. This remained broadly stable as of June-July (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Public support for migrants accessing these welfare programmes continued to be higher when considering migrants who have lived in the UK for longer periods. However, between January and June-July, support weakened—particularly for migrants working in essential occupations and for migrants from Germany, Jamaica, and Australia (Figures 5, 6, and 7). In other words, willingness for giving these migrants access to welfare programmes after they have spent five years in the UK decreased between January and June-July 2021.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Moreover, with respect to primary NHS healthcare, the UK public became less willing to grant access to longer-term migrants from EU countries over the course of the first half of 2021, although preferences did not change for newly-arrived EU migrants (Figure 5). Yet it is also important to note that preferences for extending all three types of welfare remained similar for migrants from both EU and non-EU countries.

Acknowledgements

This briefing was produced with support from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) funding through its ‘Ideas to Address COVID-19’ scheme. We also thank Dr Mathew Creighton and Dr John Kenny for their comments on a previous draft of this briefing.

References

- Claassen, Christopher, and Lauren McLaren. 2021. “Does Immigration Produce a Public Backlash or Public Acceptance? Time-Series, Cross-Sectional Evidence from Thirty European Democracies.” British Journal of Political Science: 1–19.

- Creighton, Mathew J., and Amaney A. Jamal. 2022. “An Overstated Welcome: Brexit and Intentionally Masked Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(5): 1051–71.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22(1): 1–30.

- Kustov, Alexander, Dillon Laaker, and Cassidy Reller. 2021. “The Stability of Immigration Attitudes: Evidence and Implications.” The Journal of Politics: 1–17.

- Office for National Statistics. 2010. “SOC 2010 Volume 1: Structure and Descriptions of Unit Groups.”

- Office for National Statistics. 2020. Coronavirus and Key Workers in the UK.

- YouGov. 2021. “Panel Methodology” (November 6, 2021).