This is the first briefing of a study investigating public attitudes to labour migrants in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data presented here were collected in January 2021 and correspond to the first wave of an online longitudinal survey including a conjoint experiment.

-

Key Points

- Previous research shows that public attitudes towards migration vary considerably depending on the characteristics of the migrants considered, such as their country of origin, occupational profile or reason for migration.

More… - Respondents have more positive attitudes towards migrants in jobs that have been considered essential during the pandemic by the UK Government, such as school teachers or care workers, than towards migrants in non-essential jobs.

More… - Comparing occupations of similar skill levels, respondents tend to give higher ratings to migrants in essential than in non-essential occupations.

More… - Before the pandemic, some essential occupations (care worker, nurse) were already more valued by the public based on perceptions of worthiness and social value.

More… - On average, the UK public prefers the admission of migrants coming to work in high-skilled jobs than those in low-skilled jobs and thinks the former are more beneficial to the UK economy.

More… - Attitudes are most negative towards Chinese migrants, followed by Pakistani, Romanian and Nigerian migrants.

More…

- Previous research shows that public attitudes towards migration vary considerably depending on the characteristics of the migrants considered, such as their country of origin, occupational profile or reason for migration.

-

Understanding the Evidence

The data presented in this briefing comes from a survey fielded by YouGov in January 2021 with a representative sample* in terms of age, gender, social class and education of 4,954 adults living in the UK. ... Click to read more.*Link to YouGov Panel Methodology

The data used in the briefing represents the first of a three-wave, nationally representative online panel survey carried out to inform the project Tracking Public Attitudes and Preferences for Post-COVID-19 Labour Migration Policies, which aims to track the public’s attitudes towards migrants at different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The second and third waves of the survey were fielded in April and July 2021, respectively.

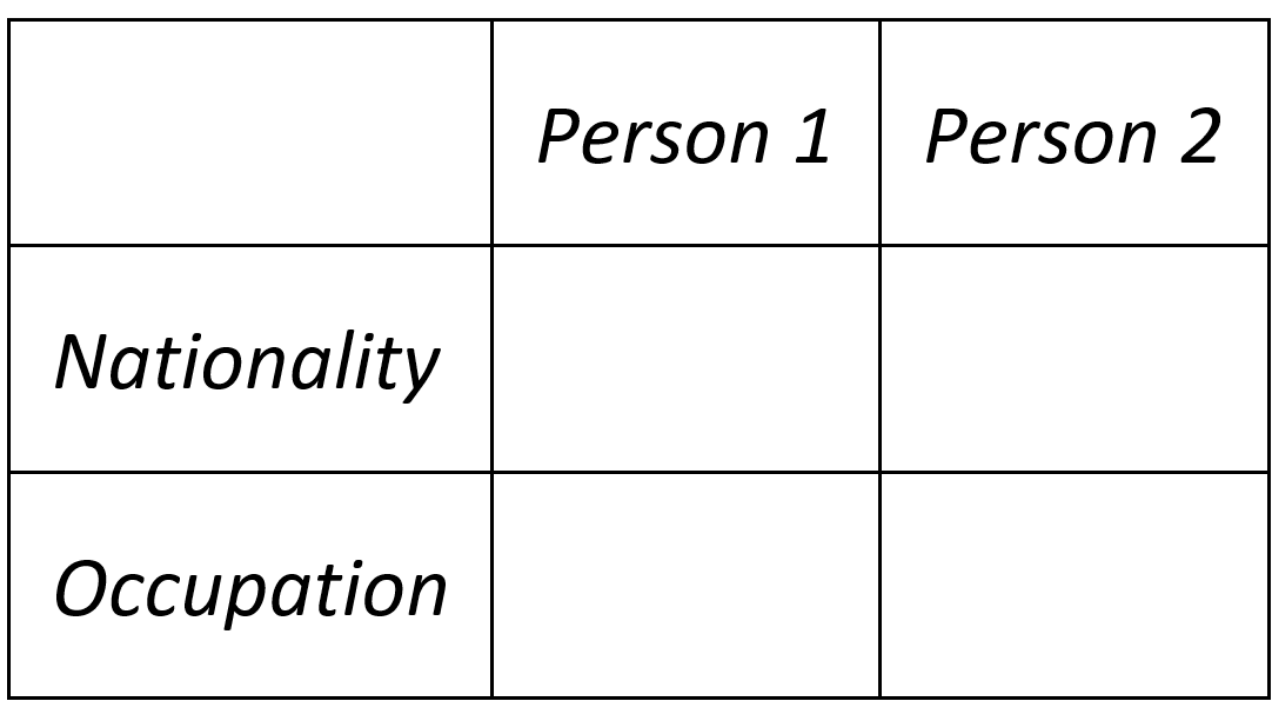

The survey consists of two parts. The first part asks respondents about their perceptions of their own situation in the labour market and how their income has been affected by the pandemic. The second part includes a conjoint survey experiment whereby respondents were presented with pairs of hypothetical migrant ‘profiles’ that vary in their nationality and occupation:

Here are the profiles of two people who could apply to enter the UK

Respondents are asked to rate each of the profiles in terms of preference for admission to the UK and benefit on the British economy:

- On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means that the UK absolutely should not admit the immigrant and 7 means that the UK absolutely should admit the immigrant, how would you rate each person?

- On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means very negative and 7 means very positive, how would you rate the impact each person on the UK’s economy?

Respondents are also ask to choose one of the profiles (binary choice question) both in terms of preference for admission to the UK and benefit on the British economy (If you had to choose, which of these two people would you personally prefer to enter the UK/do you think would be better for the UK’s economy?)

Each respondent evaluates three pairs of migrant profiles in total. We consider 12 occupations and 10 nationalities, which are randomly assigned to the two migrant profiles presented to survey respondents. The nationalities considered reflect some of the top countries of origin of migrants in the UK, key population groups in the public debate and are geographically and ethnically diverse (Australia, China, Germany, India, Italy, Jamaica, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Romania). The occupations selected have all a substantial share of migrant workers and vary with regard to skill level (low and medium-low skilled vs high and medium-high skilled, based on ONS [2010]); and essentialness (included or excluded from the UK government’s list of essential workers during the pandemic).

Methodological note about conjoint analysis

Conjoint analysis is a survey-experimental technique that estimates respondents’ preferences given their overall evaluations of alternative profiles that vary across multiple attributes (Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, & Yamamoto, 2021). Usually researchers are interested in estimating how different values of an attribute – for example, nationality or occupation – influence the probability of choosing a given profile or rating a profile with a specific score . An advantage of conjoint survey designs is that respondents are not shown all possible unique profiles (in order to estimate the effects of nationality and occupations on their preferences in our case, 12 occupations and 10 nationalities yields 120 unique combinations). For more information about conjoint analysis, see Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto (2014).

Public attitudes towards migration vary considerably depending on the characteristics of migrants, such as their country of origin, ethnicity, occupational profile or reason for migration

Public attitudes towards migration vary substantially depending on migrants’ characteristics, such as their country or region of origin, occupational profile or reason for migration . Multiple research has shown that public opinion is generally more positive towards migrants with high levels of education and/or who work in high-skilled occupations, such as engineers or doctors.

Public attitudes towards migrants in different occupations may not only vary depending on the skill level of the job they perform (in this context, job skills mainly refer to the academic qualifications and training required to perform a certain job). As the COVID-19 pandemic and the UK’s response have unfolded, certain occupations deemed essential to the country’s ability to both deal with the immediate crisis and support future national recovery efforts appear to have become more visible and valued. This is the case, for example, of some jobs that have been typically been considered low-skilled (i.e. with low educational requirements), such as care home workers or people in food manufacturing and delivery services, a large share of whom are migrants (Fasani & Mazza, 2020). According to the ONS, about 33% of the workforce in the UK are essential workers and an estimated 45% of those are in low or medium-low skilled jobs (Office for National Statistics, 2020). For more information about migrant workers in essential jobs, see the Migration Observatory briefing Locking out the keys?

Some low- and medium- skilled occupations such as care workers or nurses were also highly valued by the general public before the pandemic. For example, a survey conducted in January 2020 and commissioned by British Future and and the Policy Institute, King’s College London, revealed that more than 60% of respondents thought that care workers and nurses should be exempted from the salary threshold (Ballinger, Duffy, Hewlett, Katwala, & Rutter, 2021, p. 21).

Respondents have more positive attitudes towards migrants in jobs that have been considered essential during the pandemic by the UK Government than towards migrants in non-essential jobs

Public attitudes towards immigration do not only vary depending on migrants’ skills (that is, whether they perform a job with high or low educational and training requirements), but also based on the ‘essentialness’ or social value of the job they perform. When asked about preferences for admission to the UK, respondents rate migrants in essential jobs more highly than other migrants (Figure 1), with a score of 4.9 for ‘essential’ workers while those in non-essential jobs receive an average score of 4.3. Likewise, participants in the survey gave migrants in essential jobs a higher score (4.8) compared to those in non-essential jobs (4.5) when considering their impact on the British economy. While these differences may seem small when expressed in terms of ratings on a 1-7 scale, respondents’ preference for migrants in essential jobs are also apparent in the binary choice question (see Understanding the Evidence for detail about how this is measured). For example, on average migrants in essential jobs are chosen by respondents 22% more frequently than those in non-essential jobs when they are asked about who they would admit to the UK.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, hospital doctors for the NHS are the most likely of all migrant occupations examined to be preferred for admission (average score of 5.8), as well as the most likely to be thought of as most beneficial to the UK economy (average score of 5.6). However, not all migrants in essential occupations are preferred over those in non-essential ones (Figure 1). Engineers in a construction firm – a non-essential job, according to the UK government – are more highly valued than supermarket lorry drivers and meatpackers, which are both essential occupations.

Figure 1

Comparing occupations of similar skill levels, respondents tend to give higher ratings to migrants in essential than in non-essential occupations. For example, among low-skilled occupations, lorry drivers for a supermarket chain receive a higher rating than waiters, warehouse workers for a retailer, and administrative assistants in an accounting business (Figure 1). Likewise, among high-skilled occupations, migrants who are NHS hospital doctors, lab technicians in a pharmaceutical company or secondary school teachers receive higher ratings than those who work as IT specialists for an insurance company or as sales directors for a homeware retailer.

The pandemic may have increased the relevance and perceived value of certain jobs in low-skilled sectors, such as supermarket or care home workers. However, before the pandemic, some occupations were more valued by the public based on perceptions of worthiness and social value regardless of their income and level of education associated to them. For example, in a survey conducted in January 2020 and commissioned by British Future and and the Policy Institute, King’s College London, revealed that more than 60% of respondents thought that care workers and nurses should be exempted from the salary threshold (Ballinger et al., 2021, p. 21).

On average, the UK public prefers the admission of high-skilled migrants than low-skilled migrants and thinks the former are more beneficial to the UK economy

When survey respondents are presented with two migrant profiles, those in high- and medium-skilled occupations are rated higher than those in low-skilled jobs, both in terms of preference for admission (4.9 vs 4.3) and on their beneficial effect for the British economy (5 vs 4.3) (Figure 2). The difference in ratings for migrants in high-skilled and low-skilled jobs may seem small, but when survey respondents were presented with two migrant profiles and asked to admit just one, they were, on average, 24% more likely to choose a migrant in a high-skilled occupation than a low-skilled occupation (Figure 2). Respondents were also 24% more likely to view a high-skilled migrant as beneficial for the British economy compared to a low-skilled migrant (results based on binary choice question, which are not shown in Figure 2). This appears to be broadly in keeping with the UK government’s post-Brexit immigration policy, which is geared towards high- and medium-skilled migrant workers.

The picture changes when considering specific occupations and skill-level. Although care work in a home for the elderly is designated as low-skilled occupation (and therefore broadly ineligible to immigrate to the UK under the new points based system), respondents consider care workers roughly as deserving of admission to the UK as many of the high-skilled jobs surveyed, such as lab technicians in a pharmaceutical company, secondary school teachers, and engineers in a construction company. They are also viewed as more beneficial to the British economy than other low-skilled occupations, although less beneficial to the British economy than almost all of the high- and medium-skilled occupations considered.

Figure 2

Much of the discussion in the literature on public attitudes towards migration focuses on the preference for high-skilled over low-skilled migrants. For example, in a survey conducted in multiple European countries, including the UK, Ford and Mellon (2020) show that people generally prefer ‘professional’ over ‘unskilled migrant labourers’ (see also Migration Observatory briefing UK Public Opinion towards Immigration for data on preferences towards high- and low-skilled migration). It is possible that people consider migrants in low-skilled jobs undesirable because they assume that they will be more likely to rely on public benefits. Qualitative research shows that the British public tends to value the work performed by migrants in low-skilled jobs, but they usually are also likely to be concerned about their numbers (Bulat, 2019). At the same time, attitudes towards migrants in high-skilled occupations are not uniformly positive and people’s attitudes seem to vary depending on the social value attributed to specific occupation; for example, in a survey conducted in 2011, about a third of respondents favoured reduced high-skilled migration, but this shared increased to 40% for business and finance professionals or IT specialists.

People usually hold different ideas about the skill level required to perform a particular job, which makes attitudinal questions about low- and high-skilled migration problematic. For example, in a survey conducted in February 2020, 58% and 67% of respondents considered farm workers and care workers, respectively, to be skilled jobs, though the ONS (2010) classifies these occupations as low or medium-low skilled. Government policies, including migration policies, tend to consider only the credentials or level of education required to perform a certain job as the main criteria to classify occupations as low, medium or high skilled. In this analysis, we follow the ONS criteria although we acknowledge that there are other skills that are relevant and valued in the labour market which are not necessarily captured by workers’ level of education and training (e.g. communication skills).

Public attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic are and most positive towards Australian migrants

Migrants from China are evaluated the most negatively by respondents in our survey. On average, they receive a rating of 4.3 in terms of admission and 4.4 with regard to their benefits on the economy. Prior research on labour market discrimination in the UK did not find the Chinese minority to be the most discriminated against (Heath & Di Stasio, 2019), so it is likely that the negative evaluation of Chinese migrants is related to the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Recent works have in fact shown that Chinese nationals feel more discriminated against since the start of the pandemic (see, e.g. Wang et al., 2020 for France) and hate crime against Asians has been on the rise (e.g., Gray & Hansen, 2020 for Chinese in London; Tessler, Choi, & Kao, 2020 for Asians in the US) .

Figure 3

The reasons why people’s attitudes about migrants vary according to country or origin are complex. In Western European countries, including the UK, non-white migrants and Muslim migrants face higher levels of discrimination and public attitudes towards these groups tend to be more negative than towards other minorities (Di Stasio, Lancee, Veit, & Yemane, 2019; Ford, 2011a; Storm, Sobolewska, & Ford, 2017). Some studies attribute this disparity to perceptions of these groups as a ‘threat’ to the country’s mainstream values and culture (see Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2014 for a summary of main driver of public attitudes towards migration), particularly Western secularist values (Helbling & Traunmüller, 2020). Attitudes towards migrants from less economically developed countries are also more negative on average (Kustov, 2019), which suggests that people’s attitudes towards migrants from different countries are not only based on subjective perceptions of cultural distance.

Acknowledgments

This briefing was produced with the support of UKRI Ideas to Address COVID-19 funding. We also thank Kirstie Hewlett and Lindsay Richards for comments on a previous draft of this briefing.

References

- Ballinger, S., Duffy, B., Hewlett, K., Katwala, S., & Rutter, J. (2021). Has Covid-19 reset the immigration debate? Immigration in the new parliament. Available online

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2016). How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science, 354(6309), 217–222. Available online

- Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2021). Conjoint Survey Experiments. In Advances in Experimental Political Science. Available online

- Bulat, A. (2019). ‘High-Skilled Good, Low-Skilled Bad?’ British, Polish and Romanian Attitudes Towards Low-Skilled EU Migration. National Institute Economic Review, 248, 49–57. Available online

- Di Stasio, V., Lancee, B., Veit, S., & Yemane, R. (2019). Muslim by default or religious discrimination? Results from a cross-national field experiment on hiring discrimination. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–22. Available online

- Fasani, F., & Mazza, J. (2020). Immigrant Key Workers: Their Contribution to Europe’s COVID-19 Response. Available online

- Ford, R. (2011). Acceptable and unacceptable immigrants: How opposition to immigration in Britain is affected by migrants’ region of origin. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(7), 1017–1037. Available online

- Ford, R., and Mellon, J. (2020). The skills premium and the ethnic premium: a cross-national experiment on European attitudes to immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(3), 512–532. Available online

- Gray, C., & Hansen, K. (2021). Did Covid-19 lead to an increase in hate crimes towards Chinese people in London? Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. Available online

- Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science, 17, 225–249. Available online

- Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30. Available online

- Heath, A. F., & Di Stasio, V. (2019). Racial discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: a meta‐analysis of field experiments on racial discrimination in the British labour market. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(5), 1774–1798. Available online

- Helbling, M., & Traunmüller, R. (2020). What is Islamophobia? Disentangling Citizens’ Feelings Toward Ethnicity, Religion and Religiosity Using a Survey Experiment. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 811–828. Available online

- Kustov, A. (2019). Is There a Backlash Against Immigration From Richer Countries? International Hierarchy and the Limits of Group Threat. Political Psychology, 40(5), 973–1000. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/pops.12588

- ONS. (2010). SOC 2010 volume 1: structure and descriptions of unit groups – Office for National Statistics. Available online

- Storm, I., Sobolewska, M., & Ford, R. (2017). Is ethnic prejudice declining in Britain? Change in social distance attitudes among ethnic majority and minority Britons. British Journal of Sociology, 68(3), 410–434. Available online

- Tessler, H., Choi, M., & Kao, G. (2020). The Anxiety of Being Asian American: Hate Crimes and Negative Biases During the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 636–646. Available online

- Wang, S., Chen, X., Li, Y., Luu, C., Yan, R., & Madrisotti, F. (2020). ‘I’m more afraid of racism than of the virus!’: racism awareness and resistance among Chinese migrants and their descendants in France during the Covid-19 pandemic. European Societies. Available online