This is the second briefing of a study investigating public attitudes to labour migrants in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus of this briefing is on the public support for migrants’ access to health and welfare programmes. The data presented here were collected in January and April 2021 and are based on a survey experiment (see the ‘Understanding the evidence’ section for more information).

-

Key Points

- Previous research has shown that immigration can reduce public support for the welfare system. However, not much is known about the factors explaining this negative correlation.

More… - Public support for access to health services and welfare programmes is higher for migrants in occupations that are considered essential by the UK government in the context of the pandemic (than for those in non-essential occupations). Selected high-skilled occupations also receive stronger support from respondents.

More… - There are significant variations in the levels of support for migrants’ access to health and welfare benefits. There is higher support for access to the National Health Service (NHS) Primary Care compared to Universal Credit and Housing Assistance. These levels of support have, however, remained relatively constant over time (January vs April 2021).

More… - The longer a migrant has been in the country, the higher the support for granting them access to welfare benefits and health services.

More… - Support for access to welfare programmes does not change much when considering migrants of different nationalities. Where small differences exist, the level of support is marginally higher for Australians and Jamaicans and lower for Chinese and Pakistani nationals.

More… - Respondents whose financial situation or job schedule have been impacted by the pandemic are slightly more likely to support access to different welfare services and benefits compared to those who were not affected.

More…

- Previous research has shown that immigration can reduce public support for the welfare system. However, not much is known about the factors explaining this negative correlation.

-

Understanding the Evidence

This briefing uses data from the study Tracking Public Attitudes and Preferences for Post-COVID-19 Labour Migration Policies*. ... Click to read more.*Tracking Public Attitudes and Preferences for Post-COVID-19 Labour Migration Policies

The overall objective of the project is to understand (1) what determines public attitudes towards migrant labour and migration policies in the immediate post-pandemic period, (2) whether these attitudes are dependent on migrants’ occupation, which vary in terms of occupational skill levels and essentialness to the COVID-19 response, (3) whether attitudes vary across UK regions, and (4) the longevity of any observed attitudinal shifts, particularly in relation to the government’s efforts at developing and implementing policies for economic recovery.

The data presented in this briefing comes from waves 1 and 2 of the projects’ survey fielded by YouGov in January and in April 2021 to a nationally representative sample of 4,954 adults living in the UK. The last wave of the survey was fielded in July 2021.

The survey consists of two parts. The first part asks respondents in employment about their perceptions of their own situation in the labour market and how their income or job schedule has been affected by the pandemic. We constructed an index of the impact of the pandemic based on respondents’ answers (yes or no) to the following questions:

Think about the last week compared to your life in February 2020. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, did you (tick all that apply) …

- work fewer hours than usual?

- do more of your work from home?

- earn less money than usual?

- have to call in sick from work or stay in self-isolation?

- have to change your work patterns to care for others?

- been temporarily laid-off? [only if employed]

- been permanently laid-off? [only if employed]

- been furloughed or placed on paid leave? [only if employed]

- made any of your employees redundant? [only if self-employed]

- had trouble paying your usual bills or expenses? [only if self-employed]

- claimed self-employed income support from the government? [only if self-employed]

Respondents who were not impacted by the pandemic are those who did not tick any of the items above; those who experienced a small impact ticked one, moderate (between two and three items) or a high impact (between four and eight items.) In addition, respondents were asked about how they expect their earnings to be affected in the next six months (about the same, higher, or lower than usual).

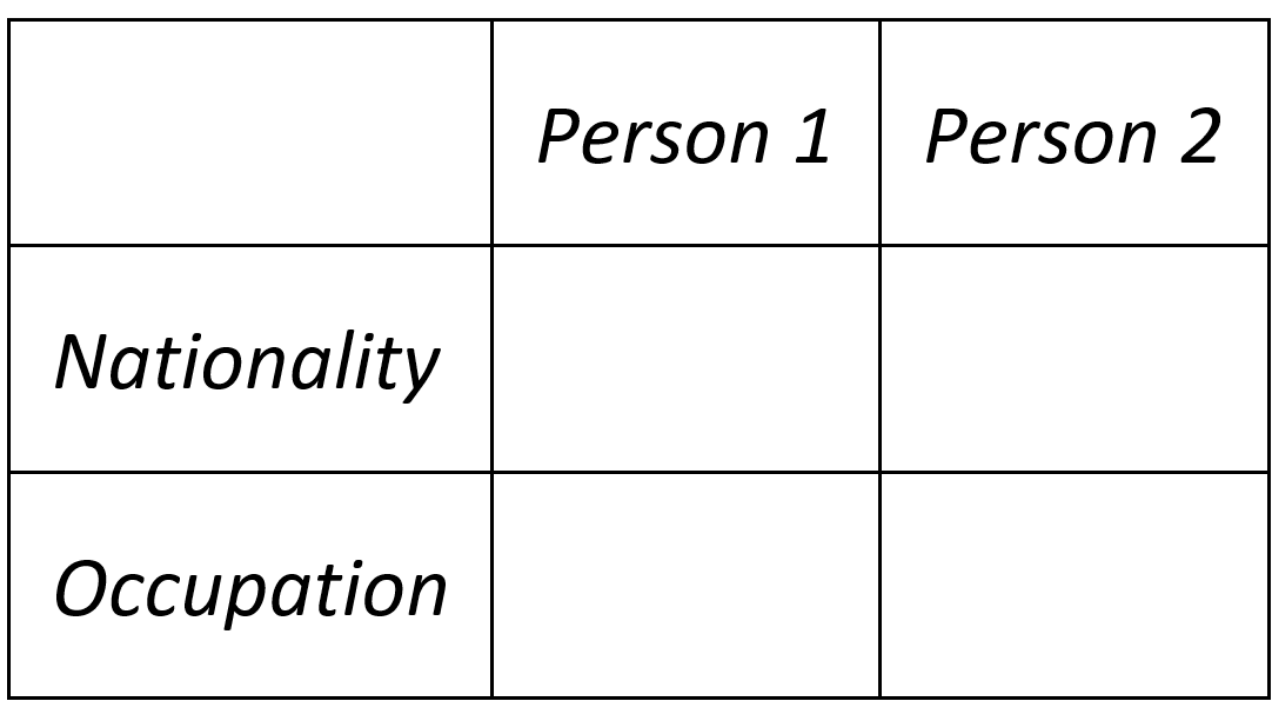

The second part of the survey presents respondents with pairs of hypothetical migrants‘ profiles. The only information that is given about these profiles is nationality and occupation.

Here are the profiles of two people who could apply to enter the UK

Respondents are asked to rate their support for person 1 and person 2 rights to access the following three benefits upon arrival and after five years of residence in the UK: Universal Credit (payment to help with living costs), Housing Assistance (financial help for housing from the local council) and National Health Service Primary Care (first point of contact for healthcare, usually a general practitioner):Imagine that Person 1/2 has just been admitted to the UK. On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means absolutely should not and 7 means absolutely should, to what extent do you think they should be able to access the following benefits [Universal Credit, Housing Assistance, NHS Primary Care] if they need them:

Next, imagine that Person 1/2 has been living in the UK for five years. On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means absolutely should not and 7 means absolutely should, to what extent do you think they should be able to access the following benefits [Universal Credit, Housing Assistance, NHS Primary Care] if they need them:

Each respondent evaluates three pairs of profiles in total. We consider 12 occupations and 10 nationalities, which are randomly assigned to the two profiles presented to survey respondents. The nationalities considered reflect some of the top countries of origin of migrants in the UK, key population groups in the public debate and are geographically and ethnically diverse (Australia, China, Germany, India, Italy, Jamaica, Nigeria, Pakistan, Poland, Romania). The occupations selected have a substantial share of migrant workers and vary with regard to skill level (low and medium-low skilled vs high and medium-high skilled, based on ONS [2010]); and essentialness (included or excluded from the UK government’s list of essential workers during the pandemic).

Methodological note about conjoint analysis

Conjoint analysis is a survey-experimental technique that estimates respondents’ preferences given their overall evaluations of alternative profiles that vary across multiple attributes (Hainmueller et al. 2015). Usually, researchers are interested in estimating how different values of an attribute – for example, nationality or occupation – influence the probability of choosing a given profile or rating a profile with a specific score. An advantage of conjoint survey designs is that respondents are not shown all possible unique profiles (in order to estimate the effects of nationality and occupations on their preferences in our case, 12 occupations and 10 nationalities yield 120 unique combinations). For more information about conjoint analysis, see Hainmueller et al. (2015).

-

Understanding the Policy

It is important to note that some of the migrant profiles featured in our survey have their access to welfare benefits and services restricted as part of the current immigration system. ... Click to read more.The ‘No Recourse to Public Funds’ (NRPF) condition applies to non-EEA residents who are subject to immigration control, which includes all people on work, study and family visas (unless they have the NRPR condition lifted due to risk of destitution). EEA citizens who arrived in the UK on or after 31st December 2020 as a visitor or a student, or with a work visa granted under the new points-based system, are subject to the NRPF condition.

Analysis by The Migration Observatory (2020), based on Home Office data, estimates that 1.4 million people are subject to NRPF. NRPF is not a blanket restriction on public services but does limit access to a number of welfare benefits and homelessness assistance. For example, those subject to the NRPF condition cannot access Universal Credit or statutory homelessness assistance. If a migrant is destitute, or at risk of destitution, they may apply to the Home Office to have the NRPF condition lifted. By contrast, primary health care services through the NHS, including GP services, are free to all migrants regardless of immigration status (PHE 2021), though secondary healthcare is chargeable.

The Home Office (2020) states that NRPF ‘is a standard condition applied to those staying here with a temporary immigration status to protect public funds (Home Office 2020). Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR) is set as the general threshold for permitting migrants to access public funds.’ Whilst considered a temporary measure, many migrants spend long periods of time subject to the NRPF condition, in particular due to changes in family migration routes lengthening the time to settlement via the five- and ten-year routes. EEA nationals who arrived in the UK on or after 30th December 2020 as a visitor or a student, or with a work visa granted under the new points-based system, will be subject to the NRPF condition.

The NRPF condition was maintained throughout the pandemic. As part of the ‘Everyone In’ scheme in England (and equivalent schemes in devolved administrations) the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (in England) requested that local authorities, ‘utilise alternative powers and funding to assist those with no recourse to public funds who require shelter and other forms of support due to the COVID19 pandemic.’

Whilst mainstream welfare benefits such as Universal Credit remained restricted, a number of schemes established in response to the pandemic were not subject to the NRPF condition, such as wages paid through the Job Retention Scheme (or ‘furlough’) and the Coronavirus Self-employment Income Support Scheme (Global Exchange on Migration & Diversity at COMPAS, 2021).

Access to primary healthcare remained unrestricted; however, research by Doctors of the World (2020) highlighted many barriers to access for migrants, including difficulties in registering for healthcare.

Previous research has shown that immigration can reduce public support for the welfare system. However, not much is known about the factors explaining this negative correlation

Whether immigration poses challenges for the support of welfare policies and the welfare system has been a longstanding question for researchers. Most recent studies have found that public support for redistribution and the welfare state decreases when immigration levels increase (Alesina and La Ferrara 2005; Alesina, Glaeser, and Sacerdote 2001). There is no consensus, however, about the factors explaining this negative correlation. Indeed, while there is a growing literature on individuals’ attitudes towards migrants, not much is known about the public’s support for migrants’ access to health and welfare programmes and whether this support is contingent on the current COVID19 pandemic and/or the migrants’ profile.

Understanding public support for migrant’s access to health and welfare benefits and services is important due to the potential impact that exclusion from these benefits and services could have on migrants’ integration. Where migrants are excluded from mainstream services and support over the long term, this could inhibit attempts at integration, for example English Language support provided via benefits agencies, or referrals to local authority services such as volunteering opportunities or support services for children, made as a consequence of access to housing support.

Public support for migrants’ access to health and welfare programmes is higher for migrants in occupations that are considered essential by the UK government the context of the pandemic (compared to those in non-essential occupations). Selected high-skilled occupations also receive stronger support from respondents

Migrant workers in essential occupations (those considered central to maintaining basic economic and public health infrastructure during the pandemic by the UK Government) have received strong public support since the beginning of the pandemic. The effort made by workers in some low- and high-skilled essential occupations (e.g. doctors, care workers or delivery drivers) has been highlighted in the British media, which possibly reinforced pre-existing positive attitudes towards some essential jobs. When asked about preferences for admission to the UK and impacts on the British economy, people report more positive attitudes towards migrants in essential than in non-essential occupations (see The Migration Observatory briefing Public attitudes to labour migrants in the pandemic: occupations and nationality for more details about this analysis).

Similarly, respondents are broadly more likely to support access to welfare programmes for migrants in essential occupations compared to those in non-essential jobs (Figure 1). The differences in ratings across occupations are, however, small in magnitude. For example, for access to the NHS upon arrival, an average rating of 4.5 is given to those in essential occupations compared to 4.2 for non-essential. Except for meatpackers, all the ratings assigned are higher for occupations that are considered essential (compared to non-essential). Unsurprisingly, the highest ratings are assigned to hospital doctors for the NHS. Average ratings for migrants in essential occupations are also higher than for those in non-essential occupations across other forms of state benefits (Universal Credit, Housing Assistance).

Figure 1

There are also notable, albeit small, differences in ratings between migrants in high- and low-skilled occupations, with those in higher-skilled jobs receiving higher support for access to welfare benefits. Note that, in this context, job skills refer to the academic qualifications and training required to perform a certain job. Care workers and supermarket lorry drivers, which are considered essential but classified as low and medium-low skilled by the ONS, enjoy higher levels of support for accessing welfare programmes compared to migrants in high-skilled occupations such as IT specialist and sales directors in homeware retailers. Care and supermarket workers were particularly lauded for their contribution during the pandemic, which may help to explain their high ratings (Figure 2).

Figure 2

In general, the highest ratings in support for access to welfare programmes are given to hospital doctors, followed by care workers and secondary school teachers (all of them essential occupations in the UK government’s list of essential workers during the pandemic) and to engineers in a construction company (non-essential but high skilled). On the other hand, the lowest ratings of support across all categories were given to sales directors (a non-essential but high-skilled occupation).

Respondents’ are more likely to support migrants’ access to NHS Primary Care than to Universal Credit and Housing Assistance. However, levels of support for access to welfare programmes have remained relatively constant over time

The average ratings show that there is higher support for access to NHS Primary Care compared to Universal Credit and Housing Assistance (Figure 3). In many ways, this mirrors the existing situation for many migrants. In addition, access to the NHS is considered to be universal and free at the point of need, whilst access to welfare benefits and housing assistance are conditional on income and other factors, such as whether a person is considered to be ‘in priority need’ for housing assistance. Previous literature has noted that universal programmes are more likely to have stronger support from the public, as all social groups benefit equally, whereas for programmes that are mean-tested (such as Universal Credit and Housing Assistance), the support is highly dependent on the identity of the recipient (Muñoz and Pardos-Prado 2019).

Figure 3

The public level of support has remained broadly constant during the first quarter of 2021. Comparing the results of the survey between January (Wave 1) and April (Wave 2) 2021, we do not see much variation in the assigned ratings (Figure 3).

The longer a migrant has been in the country, the more “support” there is to grant them access to welfare benefits

When presented with migrants who have resided 5 years in the UK versus those who have just arrived, the public seems more supportive of those who have resided longer in the UK. Figure 4 shows that these differences also hold for the different welfare programmes. This is different from the present situation where many migrants will be excluded from these programmes over the long term, in particular those on a ten year route to settlement.

Figure 4

Support for access to welfare programmes does not change much when considering migrants of different nationalities. Where small differences were seen, support was marginally higher for Australians and Jamaicans and lower for Chinese and Pakistani nationals

There are differences, albeit small, in ratings for support of access to welfare programmes for migrants of different nationalities. For example, in terms of access to NHS upon arrival, higher access ratings are given to Jamaican (4.6) and Australians (4.5), while the lowest levels are for Chinese (4.2) (Figure 5). Interestingly Germans receive higher levels of support for access to the NHS Primary Care (in the top 3) whereas they receive lower levels of support for Universal Credit and Housing Assistance upon arrival.

Figure 5

EU citizens have recently seen significant changes in their access to welfare benefits and services as a consequence of the UK’s departure from the EU and the end of freedom of movement. Those arriving after 31th December 2020 (as distinct from existing EU residents with settled or pre-settled status,) are subject to immigration control and hence subject to the NRPF condition. However, when comparing attitudes to the four EU nationalities versus non-EU there are no discernible differences in support for access to welfare benefits and NHS care.

Respondents whose employment or financial situation have been impacted by the pandemic are more likely to support access to different welfare services and benefits compared to those who have not been financially affected by the pandemic

Respondents whose employment or financial situation have been impacted by the pandemic are more likely to support migrants’ access to welfare benefits and services compared to those who have not been at all financially affected, albeit with relatively small differences (Figure 6). This relationship is not necessarily causal: respondents who have not been impacted by the pandemic may differ in significant ways from those who experienced an impact, and this may also influence their attitudes. It is also worth noting that the level of support is not significantly higher among those respondents who have been highly impacted by the pandemic compared to those who have experienced a small impact.

Likewise, respondents in employment who expect to have lower earnings than usual in the next six months show a higher support for migrants’ access to Universal Credit than respondents who expect to have similar or higher earnings than usual.

Figure 6

Acknowledgments

This briefing was produced with the support of UKRI Ideas to Address COVID-19 funding. We also thank the project team for their support in producing this briefing and to participants in our stakeholder meeting for comments on a previous draft of this briefing.

References

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2005). Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities. Journal of public Economics, 89(5-6), 897-931. Available online

- Alesina, A. E. Glaeser, and B. Sacerdote. (2001). Why Doesn’t the United States Have a European-Style Welfare State? Brookings’ Papers on Economic Activity (2), 187-277.

- Clayton, K., Ferwerda, J., & Horiuchi, Y. (2019). Exposure to immigration and admission preferences: Evidence from France. Political Behavior, 1-26. Available online

- Global Exchange on Migration & Diversity at COMPAS (2021). NRPF, COVID-19 response and the role of local government. Inclusive Cities Covid-19 response. Inclusive Cities Covid-19 Research and Policy Briefings. Issue 1, April 2021. Available online

- Doctors of the World UK (2020) An Unsafe Distance: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Excluded People in England. Available online

- Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2015). The hidden American immigration consensus: A conjoint analysis of attitudes toward immigrants. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 529-548. Available online

- Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(8), 2395-2400. Available online

- Home Office (2020). No Recourse to Public Funds. Available online

- Luttmer, E. F. (2001). Group loyalty and the taste for redistribution. Journal of political Economy, 109(3), 500-528. Available online

- Muñoz, J., & Pardos-Prado, S. (2019). Immigration and support for social policy: an experimental comparison of universal and means-tested programs. Political Science Research and Methods, 7(4), 717-735. Available online

- Public Health England (2021). NHS entitlements: migrant health guide. Available online

- Rutter, Jill, and Rosie Carter. 2018. National Conversation on Immigration – Final Report. Available online

- The Migration Observatory (2020). Between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Covid-19 Crisis and Migrants with No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF). The Migration Observatory at University of Oxford. Available online