This briefing looks at migrants whose immigration status puts them on a ten-year route to settlement in the UK, rather than the usual five.

-

Key Points

- Migrants who are given permission to remain in the UK on human rights grounds—such as children who have spent much of their lives in the UK—are often put on a ten-year route to settlement, instead of the usual five

More… - Migrants on ten-year routes face higher costs than people on the standard five-year routes

More… - The number of people granted permission to remain on ten-year family life and private life routes peaked at just over 80,000 in 2019

More… - By the end of March 2021, the estimated number of people with status on these two ten-year routes was approximately 170,000 (assuming no early switching into other statuses)

More… - Migrants entering the ten-year family life route generally did not have a mainstream family, work or study visa immediately beforehand

More… - Just over half of main applicants granted status on ten-year family and private life routes from 2016 to 2020 were from five countries of nationality (Nigeria, Pakistan, India, Ghana and Bangladesh)

More… - The number of people granted Discretionary Leave has declined since the introduction of the more formalised ten-year family and private life routes

More…

- Migrants who are given permission to remain in the UK on human rights grounds—such as children who have spent much of their lives in the UK—are often put on a ten-year route to settlement, instead of the usual five

-

Understanding the Policy

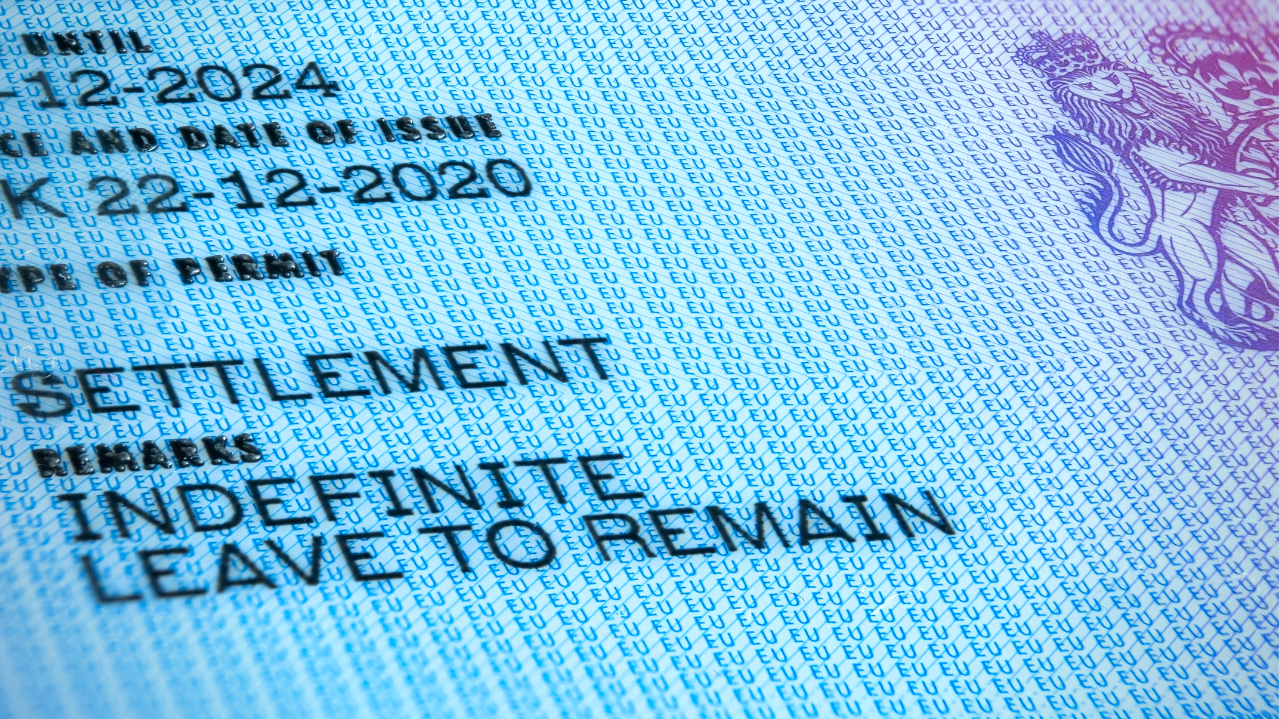

Most migrants with permission to live in the UK are eligible to settle after five years. Settlement, formally called “indefinite leave to remain”, means that the person no longer has to extend their permission to be in the UK every few years. ... Click to read more.Instead, they can remain here indefinitely without further contact with the immigration system, and progress to British citizenship if they meet the criteria.

The standard qualifying period of five years is sometimes referred to as the “five-year route to settlement”. Someone in the UK on a Skilled Worker visa will be on a five-year route to settlement, for example, as will holders of other common visa types.

Migrants who switch between different visa categories—for example, progressing from a student to a work visa—without accruing five years in qualifying categories can apply to settle after ten years under the long residence rule (paragraph 276B of the Immigration Rules). The long residence rule acts as a sort of backstop for migrants with ten years’ continuous lawful residence. This is in line with Article 3(3) of the European Convention on Establishment, a treaty ratified by the UK in 1969 (Home Office 2000).

Certain categories of migrants are placed on ten-year routes to settlement from the outset. These categories are the focus of this briefing. Put another way, we are looking at people who are on a single visa route that explicitly requires them to be in the UK for at least ten years before settlement.

Ten-year routes mostly arise from the impact of human rights legislation on the UK immigration system. In particular, section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998 makes it unlawful for a public authority (such as a government department) to act in a way which is incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights, as interpreted by the courts. This includes UK Visas and Immigration, the arm of the Home Office that deals with migrants’ applications to enter or remain in the UK. In addition, the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 requires the welfare of children to be taken into account in dealing with such applications (Home Office 2021a).

In particular, those with a family in, or long-term ties to, the UK can rely on the right to family or private life protected by Article 8 of the Convention. Article 8(1) of the Convention says that “everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence”. This right is not absolute and can be overridden by the state’s interest in maintaining effective immigration control (Halliday 2020). But Article 8 and children’s welfare considerations allow at least some migrants to secure permission to remain in the UK in circumstances where the immigration system, left to its own devices, would refuse them permission.

Such migrants are placed on a ten-year route to settlement. The provisions of the Immigration Rules relevant to human rights cases are outlined in the table below. In all such cases, migrants successfully relying on these provisions are placed on a ten-year route to settlement (Home Office 2021a).

There are four main ways that people qualify for these ten-year routes. The first two are known as the ‘family life’ category and the last two are known as the ‘private life’ category. These provisions appear in the Immigration Rules and are designed to give effect to the human rights laws discussed above.

Provision Requirements 1. Paragraph EX.1 of Appendix FM Person does not meet normal family immigration rules but either:

• has a parental relationship with British or long-term resident child and it would be unreasonable for the child to leave the UK, or

• is the partner of a British or settled person and there are insurmountable obstacles to life continuing outside the UK.2. Paragraph GEN.3 of Appendix FM • Person does not meet normal family immigration rules or paragraph EX.1, but either:

• meets every requirement bar the minimum income rule and there are “exceptional circumstances which could render refusal of entry clearance or leave to remain a breach of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, because such refusal could result in unjustifiably harsh consequences for the applicant, their partner or a relevant child”, or

• “there are exceptional circumstances which would render refusal of entry clearance, or leave to enter or remain, a breach of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, because such refusal would result in unjustifiably harsh consequences for the applicant, their partner, a relevant child or another family member”.3. Paragraph 276ADE(1) of Part 7 Person meets one of the following criteria:

• they have lived continuously in the UK for 20 years, even if unlawfully

• they are under 18, have lived in the UK for at least 7 years and it would be unreasonable for them to leave the UK

• they are aged 18–24 inclusive and have lived at least half their life in the UK

• there are “very significant obstacles” to their integration in the country of removal.4. Paragraph 276BE(2) of Part 7 Person does not fit into paragraph 276ADE(1) but there are “exceptional circumstances which… would result in unjustifiably harsh consequences for the applicant” because of the private life they have made for themselves in the UK. It is possible to invoke the second of the four provisions above to apply for permission to enter the UK on the basis of exceptional circumstances, as well as for permission to remain. The others can only be used to secure permission to remain.

In some cases, these provisions function as a means to regularisation in the UK (JCWI 2021). They are available to people who have overstayed a previous visa, which is normally a bar to securing immigration status without leaving the country and applying for a new visa to (re)-enter.

There is a certain degree of overlap between the private life and family life categories, and migrants can move between them during their ten-year journey to settlement. Those in the family life category can also move onto the five-year route should they meet the criteria after starting out on the ten-year pathway, or drop onto the ten-year route having started out on a five-year route.

Before these provisions were written into the Immigration Rules in 2012, family and private life cases were dealt with “outside the Rules”. Migrants relying on their Article 8 rights were granted a status called Discretionary Leave, with recourse to public funds and the possibility of settlement after six years. From 9 July 2012, Discretionary Leave was generally converted into a ten-year route and restricted to “exceptional and compassionate circumstances” not including family and private life considerations. This is one of several factors that complicates attempts to calculate the precise number of people on a ten-year route to settlement.

Similarly, it is also possible in principle to enter a ten-year route to settlement by being granted “leave outside the Rules” for Article 8 reasons. Such cases are now very rare in practice, but again make it difficult to establish the precise number of people on ten-year routes, as explained in more detail in the Evidence gaps and limitations section below.

Ten-year routes normally come with a condition of “no recourse to public funds” (i.e. no access to benefits), unless the person has Discretionary Leave or successfully applies to have the condition lifted (Yeo, 2019). This is possible in limited circumstances, such as where the person is at risk of destitution. A person is considered destitute if they either do not have “adequate accommodation or any means of obtaining it”, or do have accommodation but “cannot meet their other essential living needs (Home Office 2021a). The no recourse to public funds condition can later be reimposed if the person’s circumstances change.

-

Understanding the Evidence

The main data source for this briefing is the quarterly “extensions” data published by the Home Office. ... Click to read more.This shows in-country grants of immigration status (whether the person had a visa to extend or not). Grants of permission on the main ten-year routes—family life and private life—are recorded. The Home Office also publishes data on grants of other status that may be on a ten-year route—Discretionary Leave and some other grants of leave outside the Rules—although not in a way that allows five-year and ten-year pathways within those categories to be distinguished.

The figures in this briefing do not include any people who may enter ten-year routes from outside the UK rather than applying in-country.

Migrants who are given permission to remain in the UK on human rights grounds are often put on a ten-year route to settlement, instead of the usual five

The qualifying period for migrants to receive permanent status (known as settlement, indefinite leave to remain or ILR) is usually five years, but certain types of permission to remain in the UK come with an extended qualifying period of ten years before settlement is possible. This is most common where migrants do not qualify under any of the mainstream immigration routes, but where the government recognises that they have a claim to remain in the UK for human rights reasons—as explained in more detail in the Understanding the Policy section above.

People entering the ten-year ‘Family Life’ or ‘Private Life’ routes, as they are known, will usually be living in the UK and (as the labels suggest) have family ties and/or a long period of residence here. For example, a child under the age of 18 who came to the UK at a young age and is undocumented would not be eligible for any of the mainstream visa routes, but can qualify for the ten-year route on the basis of their private life if they have spent at least seven years in the UK (see entry 3 in table above).

Alternatively, someone who came to the UK on a partner visa with a five-year route to settlement might be moved to the ten-year route if their family income falls below the £18,600 usually required and they can show that there would be “unjustifiably harsh” consequences if they lost their residence rights. A more detailed description of the criteria for the ten-year routes is given in the Understanding the Policy section above. The government is obliged by human rights laws to allow this additional degree of flexibility.

The Home Office has said in the past that delaying access to settlement is a matter of principle: i.e. that migrants relying on human rights to cure what would otherwise be unlawful residence in the UK should not be allowed to settle as quickly as those who have met the requirements throughout (Court of Appeal 2014).

Migrants on ten-year routes face higher costs than people on the standard five-year routes

As the Migration Observatory briefing on Migrant Settlement in the UK explains, settlement in the UK confers a range of advantages compared to having time-limited permission to remain. Among other things, settled migrants have the security of a permanent (except in rare cases) immigration status, as well as access to state benefits.

The effect of being on a ten-year route to settlement is typically to delay the acquisition of these rights. Ten-year routes normally come with a condition of “no recourse to public funds” (i.e. no access to benefits), unless the person has Discretionary Leave or successfully applies to have the condition lifted (Yeo, 2019). This is possible in limited circumstances, such as where the person is at risk of destitution.

Ten-year routes are more expensive than five-year routes to settlement. Grants of permission to be in the UK on a ten-year route are generally issued in blocks of two and a half years’ permission at a time. The application to extend permission for an additional two and a half years costs £1,033, for both adults and children. The person must also pay the Immigration Health Surcharge, at £624 a year for adults and £470 for children, again with exceptions for Discretionary Leave. The additional financial cost of ten-year routes compared with five-year ones is therefore around £4,700 for an adult and £3,900 for a child. A child entering the ten-year route would expect to pay over £11,000 in fees before achieving settlement (Table 1), and a parent and child together would expect to pay almost £24,000.

Table 1

Cost of Ten-year Routes to Settlement, from April 2021

| Total | £12,761 | £11,221 | £23,982 | £8,065 | £7,295 | £15,360 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ten-year route | Five-year route |

|||||

| Adult | Child | Parent and child | Adult | Child | Parent and child | |

| NHS surcharge | £6,240 | £4,700 | £10,940 | £3,120 | £2,350 | £5,470 |

| Applications for permission to remain (2.5 years each) | £4,132 | £4,132 | £8,264 | £2,556 | £2,556 | £5,112 |

| Settlement | £2,389 | £2,389 | £4,778 | £2,389 | £2,389 | £4,778 |

Note: excludes cost of the life in the UK test for adults, biometric enrolment, and any legal fees. Assumes that people on the five-year route apply from outside the UK but those on the ten-year route apply in-country.

Qualitative research with migrants on ten-year routes has suggested that costs and the need to make repeated applications can lead to people losing status and having to start the ten years again (JCWI 2021). However, there are no official figures that identify the scale of this phenomenon. Another recent study found that ten-year route applicants often struggle to make applications without immigration advice, and that there are limited sources of affordable advice (Wilding et al, 2021).

It is possible to apply to have the health and visa application (but not the settlement) charges waived, but only where the person “has credibly demonstrated that they cannot afford the fee” (Home Office 2021b). Until 2021, the test applied was stricter, focusing on whether the person was destitute or would become destitute by paying the fee.

The number of people granted leave under the ten-year family or private life routes peaked at just over 80,000 in 2019

Until the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the number of people granted status on both the family life and private life routes had increased substantially. In 2019, the combined figure peaked at just over 80,000 main applicants and dependants, which is more than three times the figure in 2015 (Figure 1).

The trends for grants under the ten-year family life and private life routes are similar, although the family life route is larger. There is some overlap, however, between the family and private life routes. For example, a child may qualify under the private life route in their own right, but if their parent is also applying under the family life route, the child may instead be granted status as a dependant on the family life route. It thus makes sense, for many purposes, to consider the two routes together.

Figure 1

One possible factor contributing to the increase over time is the Supreme Court decision in the case of MM (Lebanon) and subsequent changes to the Immigration Rules and Home Office policy (Desira 2017). These changes created the second of the two family life provisions discussed in the Understanding the Policy section above.

Some of the increase in grants results is due to extensions of people who already hold status on the route, although this does not explain the overall trend. Separate Home Office figures (which exclude dependants) show that the number of main applicants newly entering the family life route more than doubled between 2015 and 2019, from 14,340 to 37,512 (Immigration Statistics Table Exe_D02).

The total number of in-country grants under these two ten-year routes fell by 36% in 2020, at the same time as the Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted much of the immigration system and saw fewer applicants and grants across the board. By way of comparison, this decline was much larger than the 15% decline in in-country grants of partner visas.

By the end of March 2021, the estimated number of people with status on the family or private life ten-year routes was approximately 170,000

Migrants on the two ten-year routes described so far in this briefing are granted status for 2.5 years at a time. This means that people currently on the routes will have been granted their status within the last 2.5 years, whether they have newly entered the route or have been on it for some time. An approximate estimate of the number of people with status on the two ten-year routes thus comes from examining the total number of grants of status during any 2.5 year period. Note that this figure will continue to include any people who switch out of the ten-year route early (something that may be possible under limited circumstances, such as parents who meet the requirements for the five-year route).

Based on an assumption that the number of people switching out of the routes before 2.5 years is very small, the estimated number of people on the family life route was 143,000 at the end of Q1 2021, in addition to 26,000 in the private life route, for a total of just under 170,000. It is not possible to say whether everyone who holds status is still present in the UK, although emigration is less common among people who have lived in the UK for long periods (Sumption and Kierans, 2020).

Figure 2

How does this compare to other migration routes? By way of comparison, by the end of 2020, 260,000 people held a valid temporary status in the family category after entering on one of the mainstream family, work or study routes (Home Office, 2021c). There is some overlap between this group and those on ten-year routes. This is because the 260,000 figure will include some people who entered on a mainstream route and then moved directly onto a ten-year route before the end of 2020, although as outlined in the next section, this is not the norm. The total number of people with valid permission to remain in the UK in any category—again, after entering on one of the mainstream work, study or family routes—was 1.3m by the end of 2020 (Home Office, 2021c). In other words, ten-year routes are now a substantial component of the overall immigration system. Note that it is not possible to calculate the percentage of visa holders who are on ten-year routes, because the 1.3m includes some, but not all, ten-year route migrants.

Migrants entering the ten-year routes generally did not have a mainstream family, work, or study visa immediately beforehand

A majority of main applicants newly entering the ten-year family life route were previously not in the UK on one of the mainstream family, work or study routes but had their previous immigration status recorded as ‘other’. This includes private life, Discretionary Leave and asylum-related permission to remain. It also includes people for whom no previous permission was identified including those with no status at all (e.g. people whose permission to be in the UK had lapsed).

From 2016 to 2020, an average of 3,130 main applicants per year moved from the five-year partner route to the ten-year family life route (Table 2). This would include people who did not meet the minimum income threshold or other criteria.

Similar statistics are not available for people newly entering the private life route. The figures for private life in Table 2 include people who were already on the private life route and applied to extend their status in the same category.

Table 2

Previous category of leave for main applicants on family and private life ten-year routes, 2016-2020 annual average

| Family Life (excluding those already on family life route) | Private Life (including those already on private life route) |

|||

| Other | 13,831 | 59% | 2,804 | 52% |

| Not recorded | 5,011 | 21% | 1,048 | 19% |

| Family life (ten-year route) | N/A | 1,184 | 22% | |

| Spouse/Partner | 3,130 | 13% | 190 | 4% |

| Visitor | 623 | 3% | 88 | 2% |

| Study | 602 | 3% | 74 | 1% |

| Work | 263 | 1% | 30 | 1% |

| Other family | 93 | 0% | 5 | 0% |

| Total | 23,553 | 100% | 5,423 | 100% |

Note: people who were already on the Private Life route cannot be excluded using available data. Caseworkers are not required to enter any information in the ‘previous category of leave’ field to process a case; as a result, some are ‘not recorded’.

Just over half of main applicants granted status on the ten-year family route from 2016-2020 were from five countries of nationality (Nigeria, Pakistan, India, Ghana and Bangladesh)

The largest group of people granted status on both the ten-year family Life and private life routes were nationals of Nigeria and Pakistan, from 2016 to 2020 inclusive. The top five countries made up 56% of grants on the two routes combined during this period.

Compared to partners applying in-country in the five-year family route, Nigeria, Ghana and Jamaica are overrepresented in the ten-year routes. Nigerians accounted for 19% of grants in both ten-year routes over the period, compared with 5% of grants in the five-year partner category, for example. Ghanaians accounted for 7% of family ten-year grants and 5% of private life grants, compared with 2% of partner grants.

Table 3

In-country grants of leave in the ten-year routes and five-year partner route, by nationality, 2016-2020 annual average (includes dependants)

| Total | 43,716 | 100% | 7,886 | 100% | 41,395 | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Life | % | Private Life | % | Partner (illustrative comparison) | % | |

| Nigeria | 8,403 | 19% | 1,518 | 19% | 1,898 | 5% |

| Pakistan | 6,052 | 14% | 1,086 | 14% | 6,562 | 16% |

| India | 4,544 | 1% | 803 | 1% | 4,504 | 11% |

| Ghana | 3,153 | 7% | 356 | 5% | 724 | 2% |

| Bangladesh | 2,522 | 6% | 486 | 6% | 1,970 | 5% |

| Jamaica | 2,134 | 5% | 559 | 7% | 511 | 1% |

| China | 1,236 | 3% | 298 | 4% | 1,900 | 5% |

| Albania | 1,396 | 3% | 97 | 1% | 473 | 1% |

| Sri Lanka | 1,088 | 2% | 251 | 3% | 1,018 | 2% |

| Vietnam | 878 | 2% | 44 | 1% | 368 | 1% |

| Zimbabwe | 695 | 2% | 205 | 3% | 261 | 1% |

| Afghanistan | 729 | 2% | 100 | 1% | 445 | 1% |

| Others | 10,886 | 25% | 2,083 | 26% | 20,761 | 5% |

Source: Migration Observatory analysis of Home Office immigration statistics, table Exe_D01. Note: Includes all in-country grants of status, whether it is the first application or an extension under the same category; entry clearance visas for partners are not included as small numbers may be on the ten-year route, but note that percentages of partner grants by nationality are almost identical when entry clearance visas are included (data not shown). Note that the figures do not include small numbers of parents granted leave to remain on a five-year route to settlement.

The make-up of the ten-year route population may reflect to some extent the make-up of the irregular migrant population, since these routes provide a pathway to regularisation. Reliable and accurate estimation of the size of the UK’s irregular migrant population has not to date been possible, let alone a breakdown by nationality. It is perhaps significant that a recent small-scale survey of irregular migrants in the UK had more Nigerian and Ghanaian respondents than any other nationality (JCWI 2021).

Another possible explanation for higher representation on ten-year routes for certain nationalities is that they reflect lower levels of financial resources in those groups, making it more difficult to access legal advice or qualify for five-year routes (e.g. due to the financial and income requirements).

The number of people granted Discretionary Leave has declined since the introduction of the more formalised ten-year family and private life routes

Discretionary Leave is essentially a label for permission to remain in the UK granted for human rights reasons other than Article 8. Home Office policy explains that granting Discretionary Leave is appropriate where there are “exceptional compassionate circumstances or there are other compelling reasons to grant leave on a discretionary basis” (Home Office 2015a). This includes, but is not limited to a terminal illness such that the person’s removal would be a breach of their rights under Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, or a “flagrant denial” of human rights in some other way.

Those granted Discretionary Leave can also be considered to be on a ten-year route to settlement. The policy is that “Where a person has held DL for a continuous period of 10 years and continues to qualify… they should be granted settlement unless there are any criminality or exclusion issues” (Home Office 2015a). The exception is for victims of human trafficking, who “are not considered to be on a route to indefinite leave to remain in the UK” (Home Office 2020), although if they were to remain in the UK for ten years they can apply for settlement under the long residence rule.

The scope of Discretionary Leave has changed significantly over the years. Between 2003 and 2012, Discretionary Leave was granted to those relying on their family or private life, as well as other human rights cases. That changed from July 2012 with the creation of the ten-year routes for private and family life applicants, taking them outside the Discretionary Leave policy altogether and leaving it as a residual human rights category. The old, pre-July 2012 version of Discretionary Leave allowed for settlement after six years rather than ten years now.

Grants of Discretionary Leave fell significantly in 2012, when the ten-year family and private life routes were created. The numbers remained high from 2013-2015, likely because those with existing Article 8 Discretionary Leave could renew it for a further three years and then settle. These extensions had largely washed through the system by the third quarter of 2015, when the last cohort of people granted the old version of Discretionary Leave would have applied for their extension. The numbers then fell sharply to around 2,500 grants a year, and further still in 2019-2020.

Figure 3

The fall in Discretionary Leave grants after 2015 is not the main driver for the increase in people granted permission in the other ten-year routes. The increase in family and private life grants, described above, took place primarily from 2017 to 2019, and was much larger than the decline in non-asylum Discretionary Leave.

Evidence gaps and limitations

Aside from the nationality and previous immigration status of people on ten-year routes, there is no published information available about this group. In response to Freedom of Information requests, the Home Office said that it did not have statistics on the age breakdown of applicants, for example, although this may become possible as the new immigration system beds in.

Similarly, there is no information on how many people ‘complete’ the ten-year routes. People on the new family and private life routes will only start to become eligible for settlement in 2022, ten years after the routes were introduced in their current form. There are also no figures on whether people who lose their status on the route subsequently reacquire it. The annual Migrant Journey publication does allow for calculation of length of time until settlement, but again is not structured in such a way that migrants originally placed on ten-year routes can be identified. The Migrant Journey user guide states that “it is not possible to separately identify migrants” granted permission on the basis of their Article 8 family life as distinct from under the normal family migration rules.

While there have been some qualitative studies identifying impacts of ten-year routes to settlement on applicants, there is insufficient statistical data to quantify them. For example, these routes may affect integration outcomes by delaying the acquisition of citizenship or affecting families’ financial stability. Lack of data and the complexity of integration make it hard to measure such effects, however.

While it is possible, at least in principle, to enter the UK on the ten-year family life route, the entry clearance data does not record such cases. There is also no published data on gender breakdown of those on ten-year routes.

We also do not know how many people with Discretionary Leave are in fact on a ten-year route, as victims of human trafficking are not considered to be on a settlement pathway.

In addition to the main three ten-year routes discussed here, some people relying on their Article 8 rights and placed on a ten-year route to settlement may be classified as having been given “leave outside the Rules”. This is particularly the case between 2012 and 2017, when private and family life considerations were only partly written into the Immigration Rules but those applying outside the Rules were no longer granted Discretionary Leave. Leave outside the Rules can however be granted for various reasons, often for short periods of time without an expectation of settlement. It is not possible from the available data to identify grants of leave outside the Rules on a ten-year route to settlement.

It is not possible to calculate the rate of refusal of applications for ten-year routes. That is because grants can be given in response to an application for a five-year route.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Sonia Lenegan, John Vassiliou, Colin Yeo, Bryony Rest, Jacqui Broadhead and in particular Alex Piletska for patiently fielding questions on this briefing, and to staff at Home Office for their feedback on a draft. This briefing was produced with the support of the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust.

References

- Court of Appeal 2014. R (Alladin) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWCA Civ 1334, paragraphs 29 and 30, accessed online.

- Desira 2017. Chris Desira, Home Office makes changes to Appendix FM Minimum Income Rule following MM case”, Free Movement, 10 August 2017, accessed online.

- Halliday 2020. Iain Halliday, There’s actually no right to family life in the UK, Free Movement, 30 July 2020, accessed online.

- Home Office 2000. Immigration Directorates’ Instructions, The Long Residence Concession, December 2000, accessed via National Archives online.

- Home Office 2015a. Asylum Policy Instruction, Discretionary Leave, version 7.0, 18 August 2015, accessed online.

- Home Office 2020. Discretionary leave considerations for victims of modern slavery, version 4.0, 8 December 2020, page 12, accessed online.

- Home Office 2021a. Family policy: Family life (as a partner or parent), private life and exceptional circumstances), version 13.0, 28 January 2021, accessed online.

- Home Office 2021b. Fee waiver: Human Rights-based and other specified applications, version 5.0, 5 March 2021, page 6, accessed online.

- Home Office 2021c. Migrant Journey 2020 Report, accessed online.

- JCWI 2021. Zoe Gardner and Chai Patel, We Are Here: Routes to regularisation for the UK’s undocumented population, April 2021, accessed online.

- Sumption, M. and Kierans, D. 2020. Permanent or Temporary: How long do Migrants Stay in the UK? Oxford, Migration Observatory, accessed online.

- Wilding, J., Mguni, M., and Van Isacker, T. A Huge Gulf: Demand and Supply for Immigration Legal Advice in London, accessed online.

- Yeo 2019. Colin Yeo, What is the no recourse to public funds condition?, Free Movement, 5 August 2019, accessed online.