‘Modern slavery’ is an umbrella term used by the government to encompass a range of forms of exploitation, including slavery, servitude, forced or compulsory labour, and human trafficking. This briefing examines the relationship between migrants and the modern slavery identification and support system in the UK, known as the National Referral Mechanism (NRM).

-

Key Points

- Of the 19,118 people who entered the NRM in 2024 as potential victims of modern slavery, 74% were non-UK nationals, and 26% were British. Among non-citizens, Albanian was the most common nationality from 2014 to 2024.

More… - Since 2016, most non-UK nationals referred to the NRM were men or boys, who may experience different types of exploitation to women and girls. Women are more likely to be confirmed as victims of modern slavery than men.

More… - In 2024, most modern slavery exploitation of non-UK nationals referred to the NRM was reported to have taken place exclusively outside the UK. NRM referrals involving overseas exploitation appear to be most likely when linked to an asylum claim, and often involve people who have travelled through Libya after leaving their country of origin.

More… - The share of people referred into the NRM who are confirmed as victims of modern slavery fell after the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 was implemented. In 2023 onwards, most people referred were not confirmed as victims.

More… - The time it takes for the government to issue final decisions on modern slavery cases increased substantially between 2014 and 2024.

More… - Since at least 2017, the majority of non-UK nationals in the NRM also claimed asylum, but most asylum claimants are not referred to the NRM. Around one in ten people arriving by small boat from 2018 to 2024 were referred to the NRM. The number of people receiving asylum as a result of being a victim of modern slavery is not published, but available data suggest it was substantially less than 8% of those granted refugee status through the asylum system between 2021 and 2024.

More… - Outside of the asylum system, people confirmed as victims of modern slavery are eligible to apply for temporary permission to remain in the UK in specific circumstances – in 2023, 113 individuals received this status.

More…

- Of the 19,118 people who entered the NRM in 2024 as potential victims of modern slavery, 74% were non-UK nationals, and 26% were British. Among non-citizens, Albanian was the most common nationality from 2014 to 2024.

-

Understanding the Policy

What is modern slavery? ... Click to read more.Modern slavery is an umbrella term that encompasses a range of forms of exploitation. People who experience modern slavery may have been exposed to: human trafficking; labour, sexual, or criminal exploitation; organ harvesting; or domestic servitude. The various types of modern slavery are explained in more detail in a report by the UK government. In all of these types of modern slavery, people are controlled or deceived into situations they cannot escape due to threats, violence, or someone taking advantage of their vulnerability.[1]

The National Referral Mechanism

The UK has signed international agreements to identify, protect, and support victims of slavery and human trafficking, and investigate, prosecute, and punish the perpetrators. The National Referral Mechanism (NRM) is the system established in the UK in 2009, designed to fulfil many of these commitments.

Bodies designated by the Home Office as First Responder Organisations can refer people to the NRM. These include divisions of the Home Office (e.g., Immigration Enforcement, Border Force, UK Visas and Immigration), the police, National Crime Agency, and particular charities (e.g., The Salvation Army, Migrant Help, Unseen UK, Kalayaan, Black Country Women’s Aid, the Refugee Council). These bodies will make a referral if they think, based on their ‘professional judgement’ and policy guidance[2], that the person is a victim of modern slavery. People cannot refer themselves to the NRM, and adults should not be referred without their informed consent.

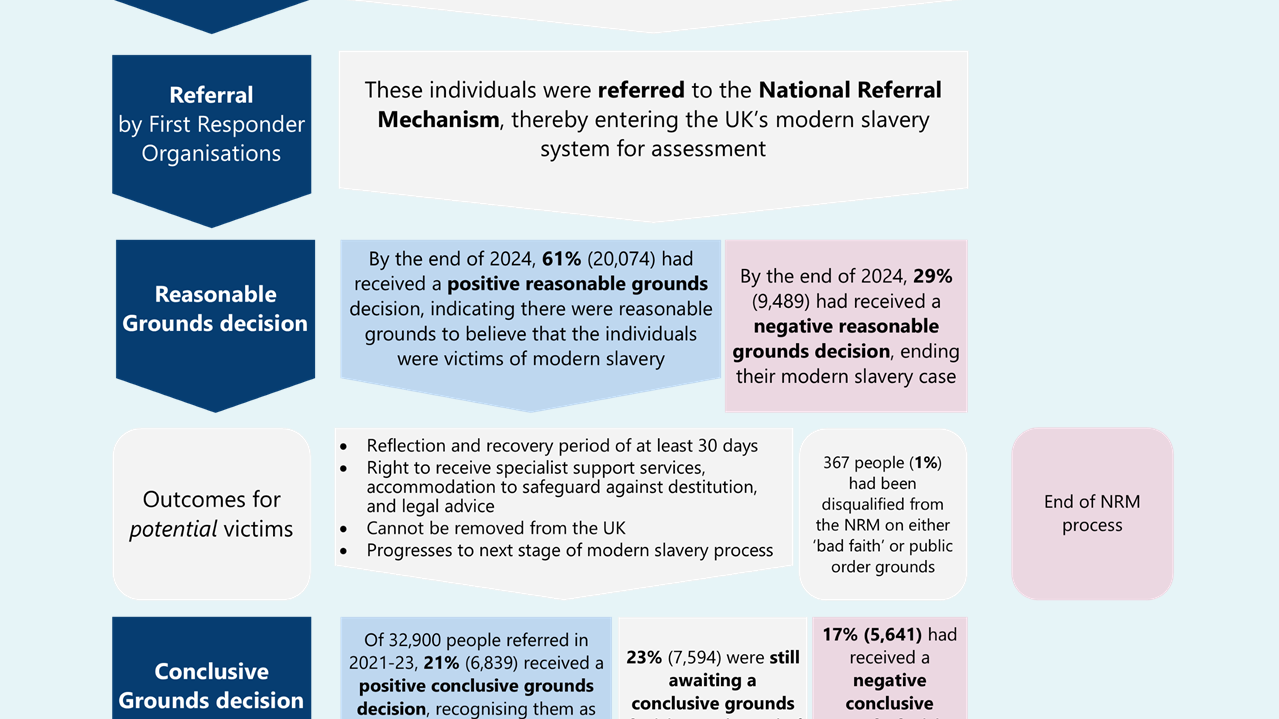

When someone is referred to the NRM, the Home Office begins a two-stage decision-making process to determine whether the person will be recognised as a victim of modern slavery. Once a person is referred to the NRM, they cannot be removed from the UK as long as the decision-making process is underway. The first reasonable grounds decision, which statutory guidance states should be made within five days of referral, is an assessment of whether there are ‘reasonable grounds’ to believe that the referred individual is a victim of modern slavery[3]. The second conclusive grounds decision is a final decision on whether a person is a victim of modern slavery.

A positive reasonable grounds decision triggers specific entitlements, including a ‘reflection and recovery period’ of at least 30 days. After a positive reasonable grounds decision, an individual cannot be removed from the UK. Individuals also have the right to receive specialist support services, such as accommodation to safeguard against destitution, and legal advice. In practice, people may face long waiting times and practical barriers to accessing these services.

Currently, if a person receives a positive reasonable grounds decision, they are generally protected from removal until they receive a conclusive grounds decision. If they are identified as a potential victim whilst in detention, they may also be released under the Adults at Risk policy if the Home Office considers that the risk of harm to the individual outweighs the need for their detention for the purposes of immigration control.

While foreign nationals are in the NRM, they are generally permitted to access emergency healthcare and education, but can only work if they have prior permission, such as if they are a British citizen or have a valid visa that permits work.

After issuing a reasonable grounds decision, the Home Office gathers further information about their case to make a final ‘conclusive grounds’ decision as to whether, on the balance of probabilities[4], the individual is recognised as a victim of modern slavery. There is no target timescale for making conclusive grounds decisions. If a migrant receives a positive conclusive grounds decision, they receive a minimum of 45 days of ‘move on’ support, which can include temporary accommodation, financial assistance to prevent destitution, psychological support and counselling, access to emergency medical treatment, translation services, and help with accessing work, training, or education. They could also be eligible to apply for permission to stay in the UK, which is typically granted for a maximum of either 12 or 30 months, and is not a route to settlement.

Some people referred to the NRM, or those with a positive reasonable grounds decision, may be disqualified from the above entitlements, either on public order grounds (because the person has engaged in serious criminality or poses a threat to national security); or ‘bad faith’ grounds (where people have knowingly lied about their case) – although disqualification will be balanced against the risk of re-trafficking.

Source: Migration Observatory and Modern Slavery and Human Rights Policy and Evidence Centre analysis of Home Office, Modern Slavery Research & Analysis (2025), National Referral Mechanism and Duty to Notify Statistics, 2014-2024, 14th Edition. UK Data Service. Notes: Reasonable grounds decisions made in 2024 will not be for the same people referred in 2024, as people receiving decisions on their modern slavery case may have been referred in previous years. Non-UK nationals are without any UK nationality and include dual nationals. At the referral stage, first responders must complete a ‘Duty to Notify’ form for those individuals (adults) who do not consent to be referred to the NRM for any reason. In 2024, there were 5,598 reports of adult potential victims who did not consent to be referred into the NRM.

The relationship between the immigration system and the National Referral Mechanism

Evidence suggests that when people do not hold the citizenship of their country of residence, or have a precarious immigration status in the UK, or both, they are at a higher risk of experiencing modern slavery.

The UK Government introduced the modern slavery identification and support system, known as the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), to comply with international agreements under international anti-trafficking law to identify and protect survivors of modern slavery—most notably the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking (known as ECAT).

There are several connections between immigration policy and the UK’s systems dealing with modern slavery. The modern slavery protection system can affect a person’s immigration process in the UK. Once someone who is not also in the asylum system has been established as a modern slavery victim (having received a positive conclusive grounds decision), the Home Secretary has a duty to grant them temporary permission to stay in particular circumstances. This permission is typically granted for a maximum of either 12 or 30 months, and is not a route to settlement. In 2024, this kind of leave was granted to 176 individuals.

For some people, an experience of exploitation may form part of an asylum claim (if that experience is related to a ‘well-founded fear of persecution’). For people who are waiting for the outcome of an asylum claim, entering the NRM could impact how long it takes for them to receive a decision on their claim. While NRM decisions and asylum decisions are not formally sequenced, and different teams within the Home Office make decisions for these two systems, caseworkers and decision-makers have stated that they felt the most significant barrier to making an asylum decision was when the individual also had a pending modern slavery case.

Legislative changes from 2022 to 2025

Two pieces of recent immigration legislation – the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, and the Illegal Migration Act 2023 (IMA) – have included measures on victim identification and support, such as widening the circumstances in which people should be disqualified from accessing modern slavery protection, including all those who enter the country without authorisation. In March 2025, the Labour government introduced the Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill, passing through Parliament at the time of writing, which repeals the majority of modern slavery measures in the IMA (which had not been operationalised), but keeps the provisions that amended the public order disqualification.

References

[1] For further information on the offences defined by the Modern Slavery Act 2015, see this information provided by the Modern Slavery and Human Rights PEC.

[2] Home Office (2023). ‘Modern Slavery: Statutory Guidance for England and Wales (under s49 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015) and Non-Statutory Guidance for Scotland and Northern Ireland’, Version 3.14, para 3.4 p.37.

[3] Section 60 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022: The Nationality and Borders Act 2022, c. 36. confirmed the reasonable grounds threshold in primary legislation, amending the test from “reasonable grounds to believe a person may be a victim of trafficking” (currently in Modern Slavery Act) to “reasonable grounds to believe someone is a victim of trafficking” (emphasis added). The Statutory Guidance uses the test of “is” rather than “may be” a victim.

[4] The ‘balance of probabilities’ threshold was confirmed in primary legislation in Section 60 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022: The Nationality and Borders Act 2022, c. 36.

-

Understanding the Evidence

This briefing mainly uses official statistics on the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) published quarterly by the Home Office ... Click to read more.This briefing mainly uses official statistics on the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) published quarterly by the Home Office. The Home Office has made its full NRM dataset available on the UK Data Service platform, which enables researchers to explore the data in greater depth. The full dataset underpins most of the analysis in this briefing.

The government’s NRM statistics are extracted from a live management information system. This means that numbers may differ from previous or future releases as new information emerges and cases are updated. Although the NRM was introduced in 2009, this briefing uses statistics from 2014 onwards, due to a change in how referrals were counted prior to 2014.

A note on terminology: some prefer the term ‘survivor’ or ‘people with lived experience of modern slavery’ when talking about the people most directly affected by this form of exploitation. This briefing also uses the terms ‘potential victim’ and ‘victim’, because these are used in the Modern Slavery Act 2015, the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (ECAT), and many other official documents and statistics.

Types of exploitation

This briefing contains statistics on the type of exploitation that the first responder organisations suspect people have experienced. Due to a change in how exploitation types were categorised from 1 October 2019 onwards, this briefing analyses exploitation data only from 2019 onwards.

The data categorise exploitation into six types:

- labour, where a person is forced to work for nothing, low wages or a wage that an employer keeps;

- sexual, where a person is exploited for sexual gratification, financial gain, or any other non-legitimate purpose;

- domestic servitude, where a person is a domestic worker who performs a range of household tasks for low or no pay;

- criminal, where a person is forced into criminal activities such as forced begging, shoplifting, pickpocketing, cannabis cultivation, financial exploitation, drug dealing, and exploitation through ‘county lines’, which refers to organised criminal networks who use children and young people to transport illegal drugs within the UK; and

- organ harvesting, where victims are recruited, transported or transferred, by threat or force for money, for their bodily organs;

- multiple, where victims are exposed to two or more of the five types listed above.

Nationality

This briefing focuses on people in the NRM – the UK’s modern slavery identification and support system – who are migrants, defined as those without British nationality. The NRM dataset records up to two nationalities for each individual and hence includes individuals with dual nationality (e.g., French-American), with no primacy given to either nationality. Dual British nationals (i.e., individuals with both British and another nationality) are excluded from the count of foreign nationals in this briefing. By contrast, individual nationality breakdowns in this briefing refer to people with only one nationality to prevent double-counting individuals under two non-UK nationalities. However, total counts of non-UK nationals include those with two non-UK nationalities.

Wait times

The Home Office publishes data on the average (both mean and median) number of days it takes for referrals to receive both reasonable and conclusive grounds decisions. These refer to the number of days between the date the referral was received and the date of its conclusive grounds decision. It is important to note that these statistics relate to cases that received a conclusive grounds decision in a given quarter. They are not a measure of the waiting time of all pending modern slavery cases. Moreover, they include any periods during which referrals may have been suspended, withdrawn, or previously closed. As such, actual average wait times will be shorter.

Who enters the national referral mechanism?

In the calendar year 2024, around 19,100 people were referred into the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), which is the UK’s system for identifying victims of modern slavery or trafficking (see Understanding the Policy, above). This was the highest annual number since the NRM was introduced in 2009. From 2014 to 2024 (the years for which comparable statistics are available), NRM referrals increased yearly, except during the pandemic in 2020.

Since 2014, most people referred to the NRM have been non-UK citizens (Figure 1), ranging from a low of 64% in 2020 to a high of 94% in 2014 and 2015. In 2024, just under three-quarters (74%, 14,155) of modern slavery referrals were of non-UK nationals.

Although large majorities of people referred to the NRM are not British, British has typically been the most common single nationality of referrals.

Figure 1

There are clear patterns in the age of referrals. Large shares of non-UK nationals referred to the NRM are adults, and larger shares of UK citizens are children (Figure 1, ‘Age’).

Since 2014, large majorities of people thought to be victims of modern slavery and referred to the NRM have been non-EU nationals (Figure 2).

Figure 2

In every year from 2014 to 2024, Albanian was the most common foreign nationality of individuals referred into the NRM. In 2024, Albanians made up 13% (2,492) of referrals, with UK nationals making up 23% (4,438) (Figure 3). The nationality composition of people referred to the NRM as potential victims of modern slavery has changed over time (Figure 3, ‘Year of referral’).

For some nationalities, there are large differences in the number of male and female referrals. Notably, in 2024, Albanian men and boys made up 85% of Albanian referrals, and 15% of all male referrals (Figure 3, Sex).

Figure 3

What is the gender and age breakdown of people referred into the NRM?

The characteristics of non-UK nationals referred to the NRM have changed over time, particularly with regard to sex, age of exploitation, and exploitation type.

There are marked differences in the types of exploitation reported for men and boys compared with women and girls. Male non-UK nationals are much more likely than female non-UK nationals to be referred to the NRM for labour exploitation (where a person is forced to work for nothing, low wages, or a wage that their employer keeps), or criminal exploitation (where a person is forced to work under the control of criminals in activities such as forced begging, shoplifting, cannabis cultivation, financial exploitation, or drug dealing). Female referrals are much more likely than males to be referred for sexual exploitation or domestic servitude (where a person performs a range of household tasks for low or no pay) (Figure 4).

Figure 4

In 2014, most non-UK nationals referred to the NRM were women or girls: 61% (the share is the same for UK nationals). That pattern has reversed over time for both UK and non-UK nationals, as the number of female referrals increased at a slower pace after 2014 than the number of referrals of men and boys. In 2024, 73% of non-UK nationals referred were men or boys (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Since 2014, slightly larger shares of male referrals have been children when compared with female referrals (Figure 6).

Figure 6

How do non-UK citizens enter the NRM?

Potential victims of modern slavery are referred into the NRM by a ‘first responder’ organisation, as explained above in ‘Understanding the Policy’. This indirectly gives some insight into where the person was when they were referred. The largest number of people entering the NRM from 2022 to 2024 were referred by UKVI. UKVI handles asylum claims, which suggests that the referrals were most likely made in connection with an asylum claim. This is consistent with data showing that most people with an NRM referral also apply for asylum (see next section).

The next most common first responder was Immigration Enforcement. These referrals will often involve people who are in immigration detention or identified in illegal working raids. As noted in ‘Understanding the Policy’, a referral into the NRM protects an individual from being removed from the UK until after a final modern slavery decision is made. In most cases, a person who is referred into the NRM from detention is released for the recovery and reflection period after receiving a positive, reasonable grounds decision. The Home Office has stated that these statistics “suggest that the prospect of having to leave the UK may act as a trigger for people to raise issues related to modern slavery, or that enforcement processes may help first responders identify potential victims.”

Other referrals come primarily from the police and local authorities, likely indicating that people were living in the community before being referred (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Non-citizens were much more likely to be confirmed as victims of modern slavery if they were referred by local authorities or NGOs, and much less likely if they were referred by Immigration Enforcement or Border Force (Figure 7, above). Referrals made by Immigration Enforcement, in particular, were most likely to be deemed ‘not credible’ (20% of negative reasonable grounds decisions for referrals made for non-citizens in 2022-2024, compared to 7% on average for all first responders).

NRM referrals from detention increased after 2019, involving a higher share of all immigration detainees. In the nine months from 1 January to 30 September 2022—the most recent period with available published data—41% of people entering detention ahead of removal were referred to the NRM while in detention (1,900 people), with almost all subsequently released from detention (1,886 people).

Figure 8

Modern slavery data do not record an individual’s method of entering the UK, or when they entered. However, the Home Office has linked NRM and immigration datasets to enable a count of the people who arrived via small boat from 2018 to 2024 and were subsequently referred to the NRM. The data suggest that people referred into the NRM and who had a final outcome (i.e., a negative reasonable grounds decision, or either a positive or negative conclusive grounds) were less likely to have a positive conclusive grounds decision if they had arrived by small boat: 23% of small boat arrivals vs. 37% of all those referred into the NRM during the same period (see Appendix 1).

Where is modern slavery exploitation reported to have taken place?

While some migrants are exploited in the UK, in 2024, 59% of non-UK nationals who entered the NRM were thought to have been exploited overseas only (Figure 9). NRM protections apply irrespective of where the exploitation happened. For example, a person may be a victim of forced labour, but this does not mean they were trafficked to the UK for this purpose.

The most common country of exploitation other than the UK is Libya. Of roughly 14,000 people referred into the NRM in 2024, for example, 23% had reported exploitation only in the UK. Another 23% reported exploitation in Libya, sometimes in combination with another country such as Sudan. In general, exploitation tended to be in non-EU countries, with 14% of people referred in 2024 reporting exploitation in an EU country.

Figure 9

Significant differences exist across nationalities in the suspected place of exploitation (Figure 10). Among the top nationalities referred into the NRM in 2024, Chinese nationals were most likely to report exploitation only in the UK. Some nationalities primarily reported exploitation that had taken place exclusively overseas. Many of these are also nationalities where a higher share of migrants in the UK have sought asylum, such as Eritreans and Sudanese. This may reflect experiences during the journey before reaching the UK, particularly for people travelling through Libya, where research suggests that forced labour is common.

Differences in the location of exploitation also reflect when and by whom non-UK citizens are referred to the NRM. For example, people reporting UK-based exploitation were most likely to have been referred by the police, local authorities, or Immigration Enforcement (perhaps following illegal working raids). People reporting only overseas exploitation were much more likely to have been referred by Border Force, presumably on arrival, or by UK Visas and Immigration, which handles asylum claims.

Figure 10

What share of people referred into the NRM are determined to be victims of modern slavery?

NRM decision-making happens in two stages, as described in the ‘Understanding the Policy’ section above. First, people receive a ‘reasonable grounds’ decision, in which the Home Office determines whether there were reasonable grounds to believe they were modern slavery victims. In 2024, 42% of reasonable grounds decisions for non-citizens were positive (the figure for UK nationals was 83%).

Second, people who received a positive ‘reasonable grounds’ decision will go on—usually after some delay—to receive a ‘conclusive grounds’ decision, where the government makes a final decision on whether people have been victims of modern slavery. In 2024, around 44% of these decisions for non-citizens were positive (i.e., the government confirmed on the balance of probabilities that they had been victims of modern slavery or trafficking).

The share of both reasonable grounds and conclusive grounds decisions that were positive declined after 2022 (Figure 11).

Figure 11

The large fall in positive reasonable grounds decisions came about after the threshold for a positive reasonable grounds decision was raised in January 2023, following a change effected by the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 and subsequent alterations to Statutory Guidance given to caseworkers. The change required potential modern slavery victims to produce “objective” evidence of their victimhood in order to receive a reasonable grounds decision, with a potential victim’s testimony not counted as objective evidence. This threshold was later suspended on 10 July 2023 by a change to caseworker guidance following a legal challenge. However, the proportions of positive decisions since the legal challenge remained at a similar level.

In 2024, the most common reason for reasonable grounds refusals was that there was insufficient information to meet the standard of proof required (54% of negative decisions), followed by cases deemed not to have met the definition of modern slavery (40%). The remaining 6% were deemed ‘not credible’.

We can combine the reasonable and conclusive grounds stages to obtain an overall rate of positive final decisions. For more recent years, many referrals had not yet received a final ‘conclusive grounds’ decision. A majority of people entering the NRM between 2017 and 2020 were ultimately confirmed as victims of modern slavery. This share is set to decline sharply for those referred in 2022 to 2024 (Figure 12).

Figure 12

Note that from 30 January 2023, the Home Office could disqualify an individual from the NRM after they received a positive reasonable grounds decision, for one of two reasons: “bad faith”, because the person is deemed to have knowingly made a dishonest statement in relation to being a victim of modern slavery; or public order grounds (e.g. following a criminal conviction). In 2024, 2% of cases were disqualified on the basis of one of these grounds, which ended these modern slavery cases.

Women have a higher rate of positive conclusive grounds decisions than men: 34% for referrals made in 2022-2024, compared with 22% for men.

How do rates of positive NRM decisions vary by nationality?

Final NRM outcomes vary by nationality (Figure 13). Looking at people referred into the NRM from 2017 to 2021 inclusive (this excludes later years where larger shares have yet to receive a final conclusive grounds decision), Ethiopians were most likely to be confirmed as victims of modern slavery (74% of those with conclusive grounds decisions), while Iranians were the least likely (34%).

Figure 13

In 2024, the share of people receiving positive reasonable grounds decisions fell across all of the most common nationalities compared with 2022, but falls were much larger among non-UK nationals (Figure 14; Decision: Reasonable Grounds).

Figure 14

Similar to reasonable grounds decisions, in 2023 and 2024, the share of people receiving positive conclusive grounds decisions was lower than in prior years across all of the most common nationalities, though falls were much larger among non-UK nationals (Figure 14; Decision: Conclusive Grounds).

How long do NRM decisions take?

The annual number of NRM referrals has increased over the past decade. However, decision-making on modern slavery cases (of all nationalities) has not seen a corresponding increase (Figure 15).

Figure 15

This disparity has created a growing backlog of unresolved modern slavery cases. Of the 125,772 cases of all nationalities referred to the NRM in the eleven years from 1 January 2014 to 30 September 2025, 92% (115,878) had been resolved as of early October 2025, meaning they had received a conclusive grounds decision, a negative reasonable grounds decision, or had been suspended, withdrawn, or disqualified. The remaining 9,894 cases were awaiting a reasonable grounds decision (787), or after having received a positive reasonable grounds decision, were awaiting a conclusive grounds decision (9,107).

A major driver of the pre-2023 growth in the backlog of modern slavery cases is that it took longer for conclusive grounds decisions to be made (Figure 16). For all conclusive grounds decisions made in 2014 (across all nationalities), the average (mean) time from referral to a conclusive grounds decision was 90 days. For decisions made in 2024, the mean wait time from referral was 831 days (around 2 years and 3 months.

There are significant differences in waiting times for conclusive grounds decisions across nationalities. Non-UK nationals typically wait much longer for their conclusive grounds decisions than UK nationals (Figure 16).

Figure 16

The Home Office credits the longer-term slowdown in decision-making since 2014 to the number of NRM decision-makers not keeping pace with increasing referrals. In evidence to the Home Affairs Committee, a senior official suggested that other causes of delays included under-resourcing and slow gathering of the information required to make decisions.

What is the relationship between NRM referrals and asylum claims?

A positive NRM decision can sometimes lead to a grant of asylum, for example, if the Home Office deems the applicant to be at risk of being re-trafficked. In other cases, people referred into the NRM may have an asylum claim that is unrelated to the reported exploitation, for example, where exploitation took place on the journey after leaving the country of origin. However, being in contact with the asylum system may make it more likely that the suspected modern slavery comes to light.

Being confirmed as a victim of modern slavery does not in itself grant long-term immigration status in the UK, as discussed in the next section. If a person wants to remain in the UK long term, the main mechanism for doing so is therefore the asylum system. However, not all non-citizens in the NRM want or need to apply for asylum. Some will already have another immigration status (such as Romanians who arrived under free movement, for example).

The Home Office has published analysis of how individuals in the NRM interact with the immigration system, looking at the period 1 January 2017 to 30 September 2022. While most asylum claimants are not referred to the NRM (9% of asylum claimants were referred to the NRM from 1 January to 30 September 2022, the period covered in the analysis), most non-UK citizens who are referred into the NRM did also make an asylum claim: 73% of all referrals in these nine months (6,701 people).

Figure 17

For people who have claimed asylum in the UK and received an initial government decision on their claim, being in the NRM does not appear to increase the chances of receiving a grant of asylum or other permission to stay at initial decision (Figure 18). In every calendar year from 2010 to 2023, asylum claimants who had also been referred to the NRM (either before or after receiving an initial asylum decision) had a lower initial decision grant rate than asylum claimants who had not entered the NRM.

Figure 18

As a result, 8% of people who were granted asylum between January 2021 and September 2024 had been referred into the NRM. However, this does not mean that all the asylum grants resulted from a positive NRM decision. Some of the 8% will not have received a positive decision, while others will have received asylum for reasons unrelated to the modern slavery claim. This suggests that a relatively small share (likely substantially less than 8%) of asylum grants resulted from the modern slavery system.

Can confirmed victims of modern slavery remain in the UK without an asylum claim?

If people are confirmed as victims of modern slavery, they receive a minimum of 45 days of ‘move on’ support, which can include temporary accommodation, financial assistance to prevent destitution, psychological support and counselling, access to emergency medical treatment, translation services, and help with accessing work, training, or education. They may also be eligible to apply for a visa that typically allows them to remain in the UK for a maximum of either 18 or 30 months. This is known as VTS leave (Victim of Human Trafficking or Slavery).

Few people are granted this form of permission to stay in the UK. In 2024, 4,240 non-British nationals were confirmed as victims of modern slavery, but only 176 received a grant of VTS leave to assist with their recovery. This is not designed as a route to settlement. Home Office guidance states that the policy intention of granting this immigration status is to allow people to remain in the UK if it is necessary to assist with their recovery, to enable them to seek compensation, or to cooperate in the investigation and prosecution of their exploiters. This was narrowed in 2023, following the introduction of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, to exclude those capable of applying for compensation outside the UK and those disqualified on public order grounds.

In practice, the limited use and duration of VTS leave means that asylum claims are the main way that victims of modern slavery remain in the UK long term.

Evidence Gaps and Limitations

There are several limitations of the available data on non-UK nationals and the NRM.

First, there is a lack of data on the link between people referred to the NRM and their immigration status, such as whether they have claimed asylum, and the status of those claims. Data on NRM referrals and decisions are recorded on a different system than data on an individual’s immigration status. Yet occasional, ad-hoc releases, such as those in response to FOI requests, and the aforementioned Annex analysing NRM referrals from asylum, small boats, and detention cohorts, suggest it is possible to link these two datasets. It would be helpful to have such data routinely collected and published on the number and characteristics of people referred to the NRM who claim asylum, and their asylum outcomes. More broadly, there is minimal data available on the immigration status of people referred to the NRM, such as whether they have EU pre-settled or settled status, or the type of visa they are on, if they have one.

Second, there are no official published data on how long people have lived in the UK or the method by which those referred to the NRM entered the UK, except for those who arrived by small boat.

Third, there are no data on exploitation broken down by the sector in which the exploitation occurred. This would be helpful in testing qualitative evidence suggesting that certain industries, such as social care, are particularly high-risk sectors for exploitation.

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful for contributions from the Modern Slavery and Human Rights PEC team and Dr Marija Jovanovic. Thanks also to Guy Dampier for comments on a previous draft.

This research was made possible thanks to the support of Oak Foundation and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), which funds the Modern Slavery and Human Rights Policy and Evidence Centre. The views expressed in this briefing are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

Appendix 1: Small boats data

Of the roughly 149,000 people who arrived by small boat from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2024, 12% (around 18,000) were referred into the NRM. This is similar to the share of all asylum claimants referred to the NRM, suggesting that people arriving via small boat are about equally likely as all asylum applicants to be referred to the NRM.

Most people in the NRM do not arrive by small boat. Between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2024, around 67,000 non-UK nationals were referred to the NRM. In the same period, around 18,000 small boat arrivals were referred, meaning that around 27% of people referred to the NRM during this period arrived by small boat.

Note that the absolute number of small boat arrivals each year who are referred to the NRM is likely to increase over time as more people from this cohort are identified by first responders as potential victims of modern slavery and referred to the NRM.

Of the 16,801 people who arrived by small boat from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2024 and who have received reasonable grounds decisions, 53% (8,862) received positive reasonable grounds decisions, meaning that the Home Office determined that there were reasonable grounds to believe these individuals were modern slavery victims. Of the 6,374 of these who had received conclusive grounds decisions, 48% (3,086 people) were confirmed as victims of modern slavery. This is similar to the average for all NRM referrals. Note that this number (and the percentage) will change over time as more people who arrived by small boat receive conclusive grounds decisions.