The idea that the UK is a particularly attractive destination for migrants is a regular theme of media and policy debates. This briefing looks at levels of migration to the UK, how the UK compares to other EU countries, and evidence on what factors drive migration to the UK. It is part of a Full Fact project to inform the 2015 General Election.

-

Key Points

- From September 2010 to September 2014, an estimated annual average of 478,000 non-British citizens moved to the UK intending to stay 12 months or longer.

More… - Economic and labour market factors are a major driver of international migration and work is currently the main reason for migration to the UK.

More… - Language, study opportunities, and established networks are all factors that encourage people to migrate to the UK.

More… - The UK has relatively high numbers of migrants in comparison to other EU countries, but has neither the highest in absolute terms nor the biggest share of migrants in the population.

More… - Immigration policy is not the only policy that affects migration flows; others include policies on employment and trade, among others.

More…

- From September 2010 to September 2014, an estimated annual average of 478,000 non-British citizens moved to the UK intending to stay 12 months or longer.

From September 2010 to September 2014, an estimated annual average of 478,000 non-British citizens moved to the UK intending to stay at least 12 months

There are different ways to measure migration to the UK, and all of them have limitations. One of the most commonly used data sources is the International Passenger Survey (IPS). This looks at migration of people intending to stay for at least 12 months.

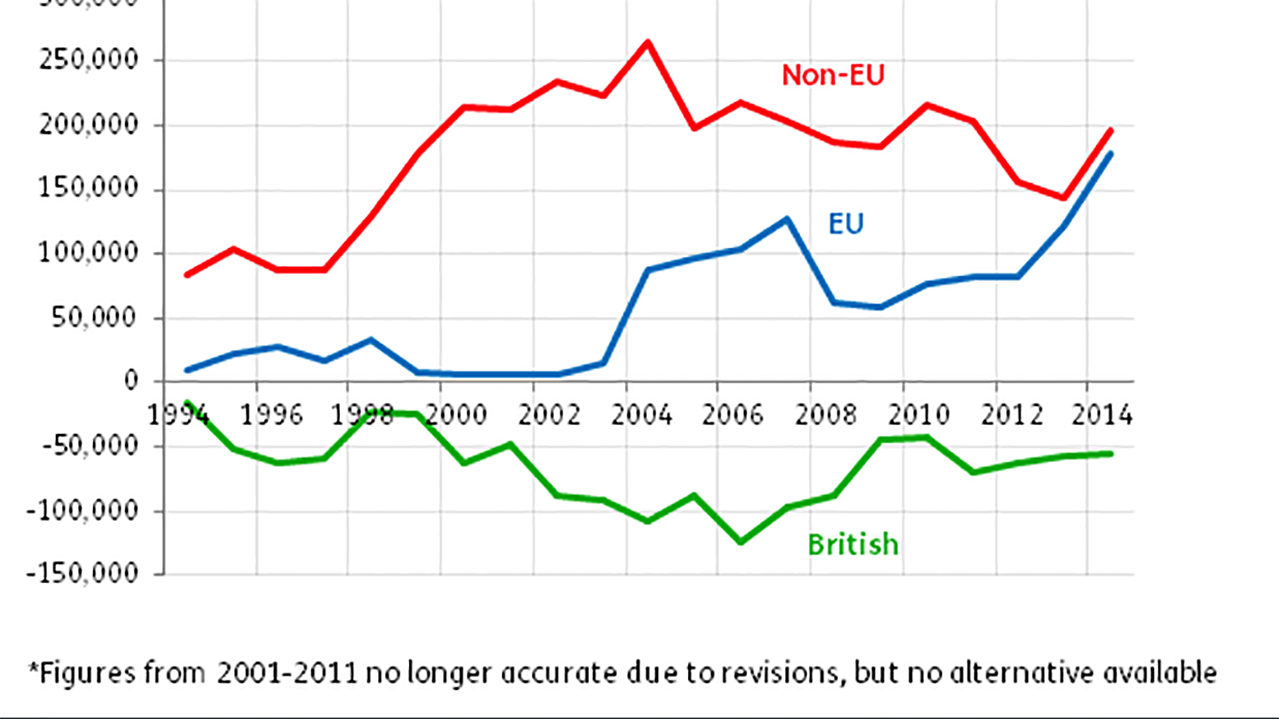

Using this measure, immigration of non-British nationals averaged 478,000 in the four year period from September 2010 to September 2014. An average of 190,000 non-British nationals ’emigrated’ (i.e. left intending to stay away for at least 12 months) each year during this period, leading to net migration of 288,000 non-British citizens on average.

The year to September 2014 saw 543,000 non-British nationals move to the UK. While this appears at first glance to be the highest inflow number on record since 1991, recent years’ immigration data cannot be compared directly to data from the mid-2000s. This is because the survey on which these immigration numbers are based undercounted migration during the 2000s, including at the time of the most recent peak in 2006.

The ONS has since revised its net migration figures, adding between 40,000 and 67,000 per year for each year from 2005 to 2008. Similar revisions of immigration figures and of net migration by nationality, used in the table above, are not available.

Economic and labour market factors are a major driver of international migration

The UK’s labour market is thought to be a significant draw for migrants from both within the EU and from non-EU countries. economic growth and the demand for specialists in certain occupations increase demand for both high- and low-skilled labour.

Income inequality in the UK over the past decades also appears to have played a role in attracting high-skilled immigrants, because it means that these people can often command high incomes in the UK. For low-wage jobs, the UK’s flexible labour market and a range of other policies have played a role in drawing in workers from the European Union. (Note that UK immigration policies do not allow employers to bring non-EU workers to the country for low skilled jobs).

Work is currently the main reason for migration to the UK

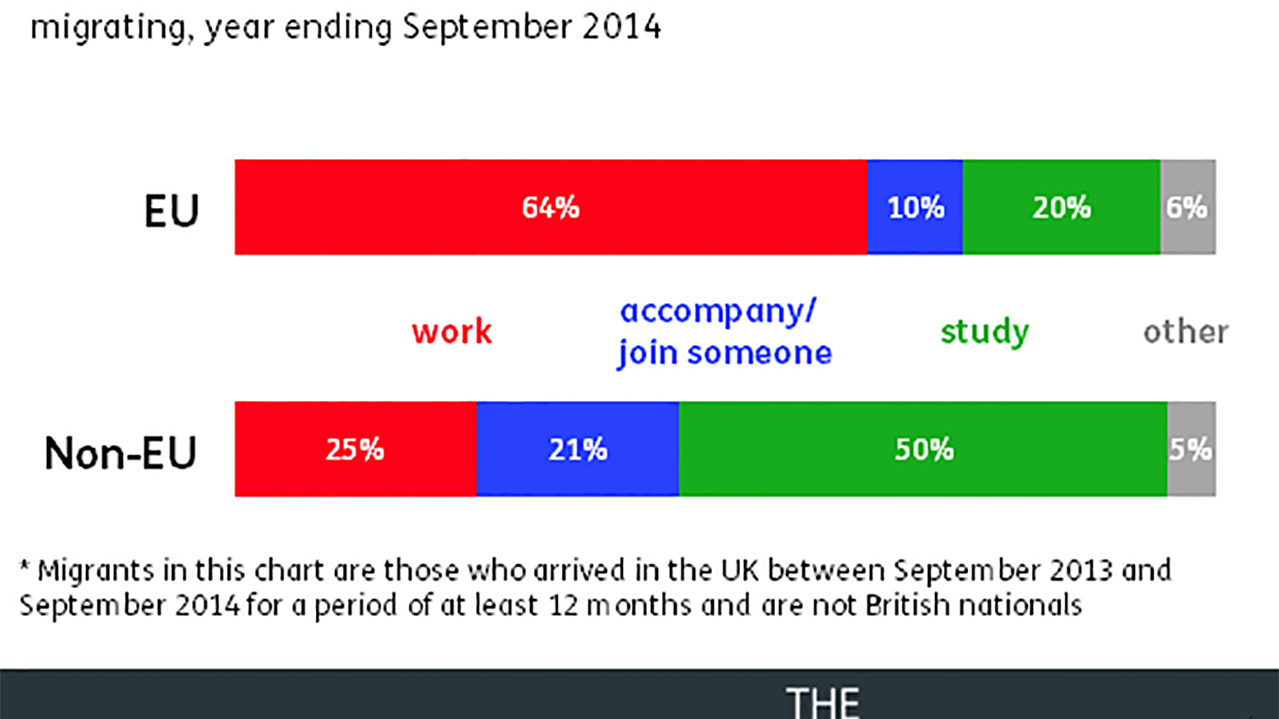

Between September 2013 and September 2014, the most common reason non-British citizens reported for coming to the UK was work. About 214,000 (43%) came for work, followed by those who came for study (179,000 or 36%). Family reasons for migrating were reported by 77,000 or 16% of migrants.

EU citizens were particularly likely to report coming for work, while non-EU citizens are more likely to report coming for family or study. Among EU citizens, the highest shares coming for work were seen among citizens of new Eastern European member states.

A relatively large share of foreign citizens gaining permanent or long-term residence rights in the UK (just under two fifths) were classified as employment-based migrants, compared to most other wealthy countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and for which data is available. This excludes EU citizens exercising free movement rights, most of whom also report coming for work (as described above). Relatively fewer came for family reasons.

Language, study opportunities, and established networks are all factors that encourage people to migrate to the UK

Existing family and community networks in a country are thought to facilitate new migration by lowering the risks of migration and support people after they arrive. These networks can facilitate job search and lower the costs of housing and childcare. Similarly, cultural and historical links with other countries (such as former commonwealth countries) are thought to facilitate migration. So, to some extent, the UK’s history of migration is likely to be a contributor to current migrant inflows.

Language also plays a role. The ubiquity of English as a second language around the world is likely to be an important factor in many people’s decisions to choose the UK as a destination.

Finally, UK universities and colleges are a significant reason for international migration to the UK. The UK had the second highest number of international students after the United States in 2013, according to the Institute of International Education.

The UK has relatively high numbers of migrants in comparison to other EU countries, but has neither the highest in absolute terms nor the biggest share of migrants in its population

One of the best available data sources for comparing migration in the UK with other EU countries is the 2011 censuses undertaken by EU member states. While this is now a few years old, other data sources do not allow the same sort of direct comparison of migrants’ characteristics. Comparable data are available for 12 EU countries that were members of the EU before 2004, including the UK.

In absolute terms, in 2011 the UK had the second highest population of foreign born people (8.0 million) after Germany (11.3 million). The UK also had the third highest population of foreign nationals (5.1 million) after Germany (6.1 million) and Spain (5.2 million).

Because the UK is one of the EU’s most populous countries it is perhaps not surprising that it has a larger number of migrants than smaller member states. The share of migrants in the population can be a more useful measure than absolute numbers when looking at the role of migration in a given country.

When considering the share of either foreign born or foreign nationals in the population, the UK ranks slightly lower down the list of comparable old EU member states than it does when looking at absolute numbers.

Among the 12 old EU countries for which comparable data are available, the UK had the fifth highest share of foreign born (13%) in its population in 2011 and the fifth highest share of foreign nationals (8%) in its population. Luxembourg, Ireland, Germany and Sweden all had higher shares of foreign born people than the UK.

Looking only at foreign nationals (and thus excluding naturalized citizens), Luxembourg, Ireland, Spain and Greece had a higher share than the UK. Countries with a lower share of both foreign born people and of foreign nationals in 2011 included France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Italy and Portugal.

Immigration policy is not the only policy that affects migration flows; others include policies on employment, welfare and trade (among others)

Shifts in immigration policy can alter the scale and composition of migration inflows and outflows by affecting who is eligible for a visa to come to the UK or to settle here. However, the relative importance of policies in affecting the number of migrants and in explaining changes over time has been debated.

Immigration flows often fluctuate in the absence of significant changes in policies. The increase in EU migration between 2010 and 2014 is one example of this. Similarly, the number of non-EU migrants coming to the UK for work increased by an estimated 24,000 from the year ending September 2013 to the year ending September 2014 even though policies had not become more generous during this period. The UK’s economic recovery is likely to have played a role in both cases.

Research has pointed to several other policies that affect immigration flows in addition to immigration policy. These include areas such as labour market regulation, macro-economic policies, and trade. Because these policies affect employers’ recruitment practices and the market in which they operate, they result in higher or lower demand for certain groups of workers, including newly arriving migrants.

Related material

- Migration Observatory briefing – Long-Term International Migration Flows to and from the UK

- Migration Observatory briefing – Migrants in the UK: An Overview

- Migration Observatory briefing – The Labour Market Effects of Immigration

- Migration Observatory briefing – Migration Flows of A8 and other EU Migrants to and from the UK

- Migration Observatory commentary – Romania and Bulgaria: The Accession Guessing Game

Thanks to Martin Ruhs, Bridget Anderson and Joseph O’Leary for helpful comments on a previous version. This work has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation but the content is the responsibility of the authors and of Full Fact, and not of the Nuffield Foundation.