Discussions of the numbers, characteristics and impacts of migration often focus on the UK as a whole. However, migration patterns differ substantially by local area. This briefing discusses evidence on the characteristics and impacts of migration at the local level, focusing on the impacts on public services. It is part of a Full Fact project to inform the 2015 General Election.

-

Key Points

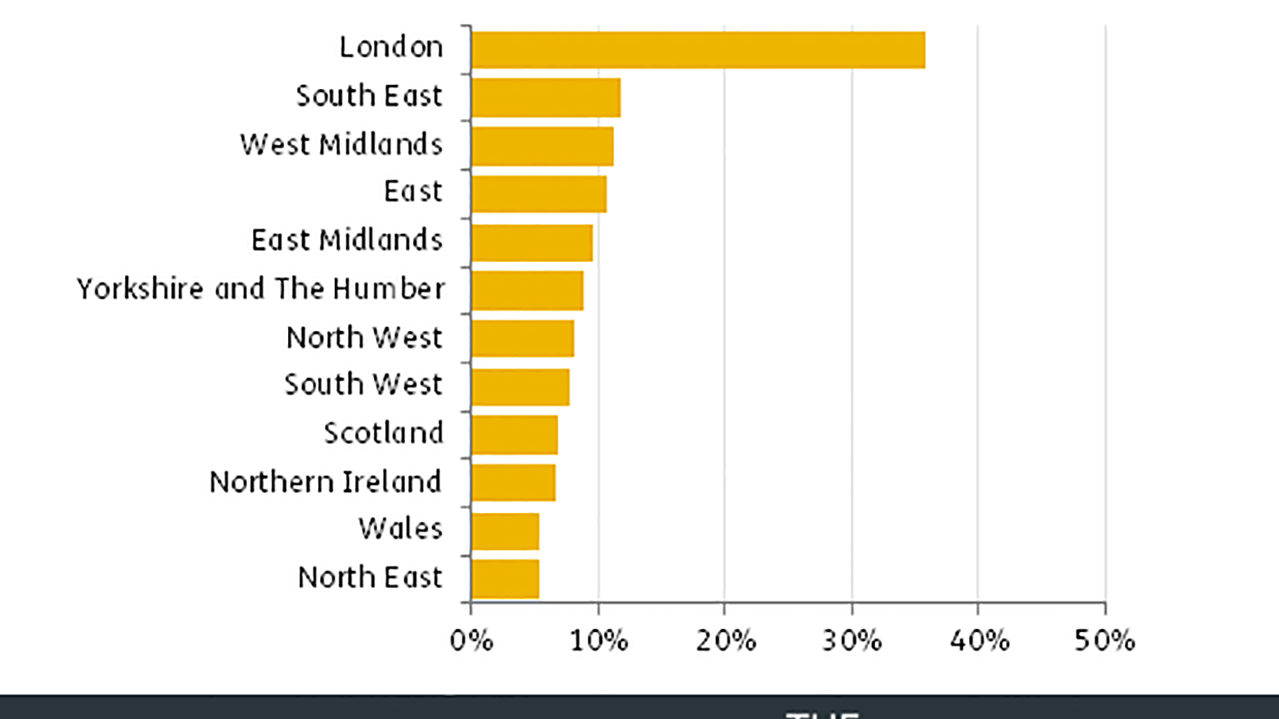

- Some areas within the UK have experienced higher levels of migration than others. London is the region with the highest share of foreign born people in its population, while the North East has the lowest share.

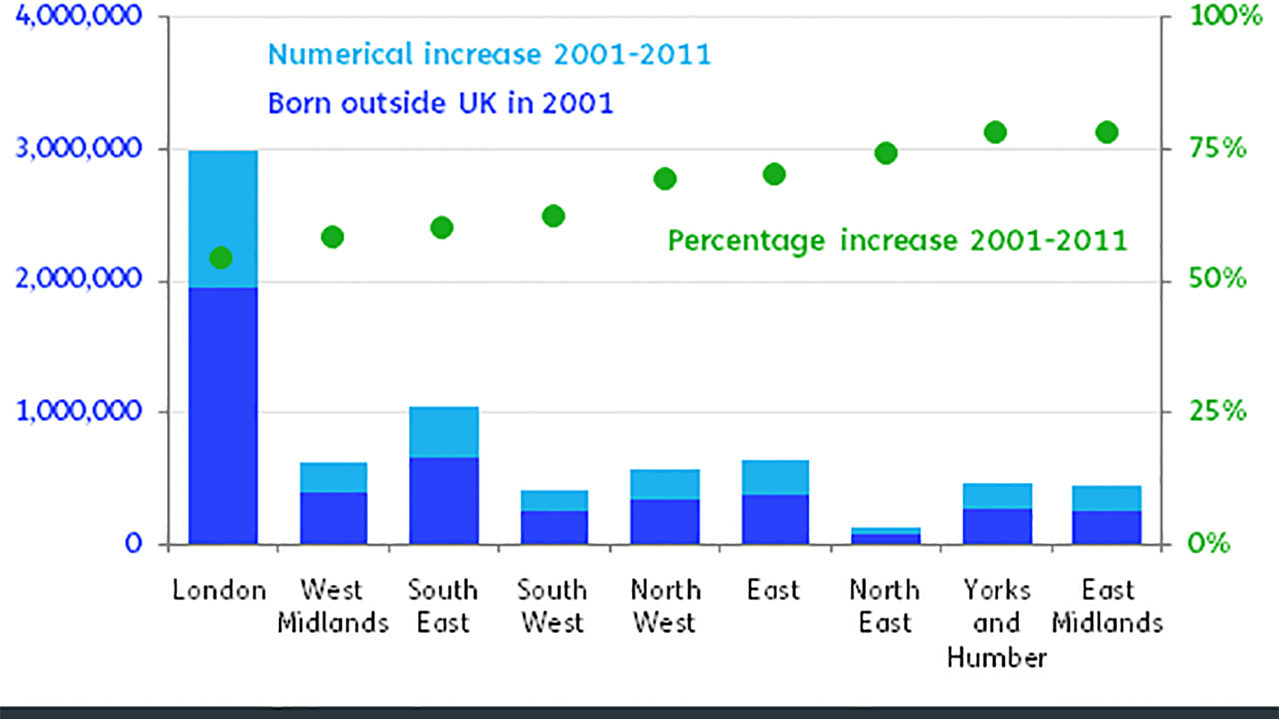

More… - Looking at more recent trends, increases in the foreign-born population during the 2000s varied regionally, with the largest percentage increases in the East Midlands and in Yorkshire and Humber.

More… - It is not possible to say with certainty what the implications of migration are for the cost, availability and quality of public services, and these impacts are likely to vary by area and depending on the type of public service.

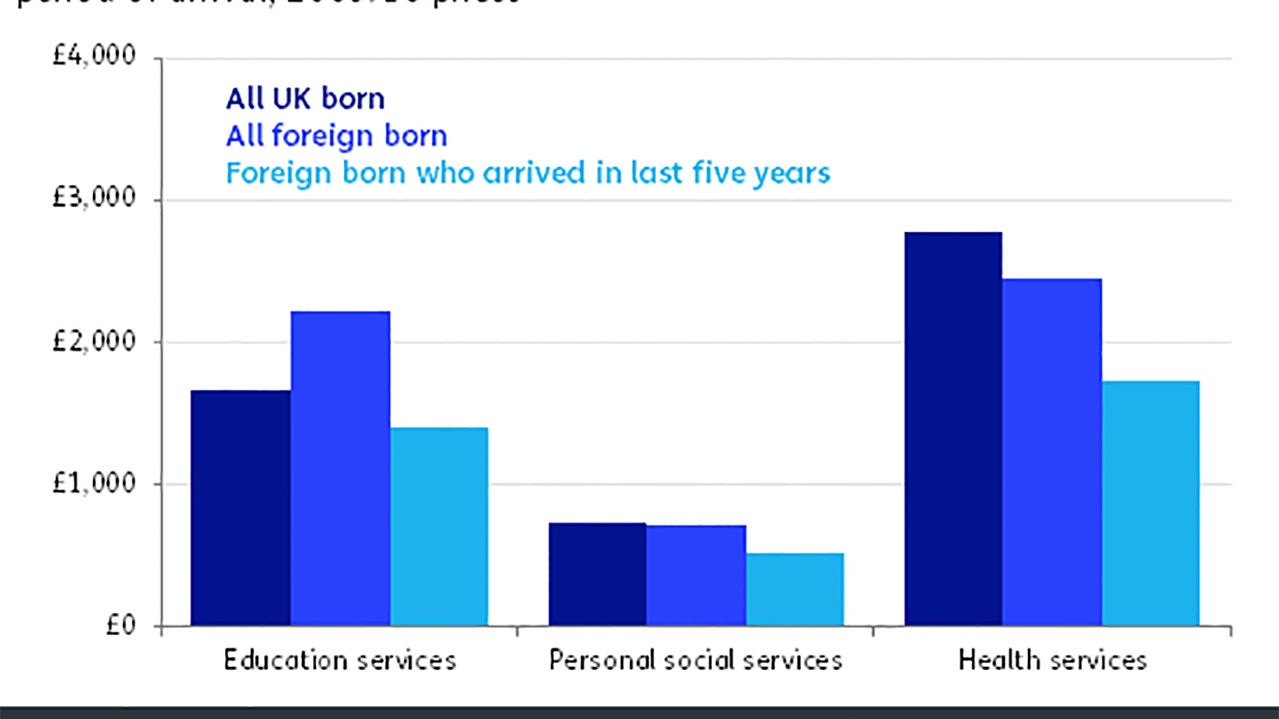

More.. - Migrants contribute to demand for public services. If foreign-born people in the UK used public services in the same way as demographically similar UK-born people, they would be expected to make less use of health and social care, but greater use of education.

More… - Migrants also contribute to financing and providing public services, and are overrepresented in the health care and social care workforces.

More…

- Some areas within the UK have experienced higher levels of migration than others. London is the region with the highest share of foreign born people in its population, while the North East has the lowest share.

Some areas within the UK experience higher levels of migration than others. London has the highest share of foreign born people in its population, while the North East has the lowest

In 2013, 12.4% of the UK population was born abroad, according to Office of National Statistics estimates. This share varied by region. 36% of the population of London was born abroad, compared to 5% of the population of the North East.

All of the top ten boroughs with the highest shares of foreign born people in their populations were in London, with the highest share in the London Borough of Brent. The local authority with the highest foreign-born population share outside of London was Slough, with an estimated 41% of residents born outside of the UK in 2013.

Some local authorities, by contrast, have very low levels of migration. In Redcar and Cleveland in North Yorkshire, for example, foreign born people made up just 2% of the population.

Looking at more recent trends, increases in the foreign born population during the 2000s varied regionally, too

According to information from the 2011 Census of population in England and Wales, the London region experienced the largest increase in its foreign-born population since 2001. However, since London already had the largest number of non-UK born residents in 2001, this increase of 54% did not represent the highest percentage rise in foreign-born population, but the lowest.

Yorkshire and Humber and the East Midlands regions experienced the highest percentage increases in their non-UK born population between 2001 and 2011, both increasing by 78%.

The impacts of immigration on local public services are difficult to identify precisely

The most comprehensive review of the impacts of migration on services was conducted by the Migration Advisory Committee in 2012. It pointed to serious difficulties in accurately measuring the effects of migration on the availability and quality of public services.

A major reason for this is the lack of information on the nationality or country of birth of people who use public services. Some general observations are possible, however.

First, because migration increases the population, it increases the number of potential users of public services.

- The extent to which migrants rely on public services will vary depending on the characteristics of migrants and on the service in question. For example, newly arriving migrants tend to be young adults. Because of their age, they are expected to be less likely to use adult social care and most health services than the UK born. However, they are more likely than the UK born to have young children, and so they are expected to rely more heavily on education and maternity care.

- A study using data from 2009-2010 estimated what the spending per head on various groups of foreign-born residents would be if they used public services at the same rate as UK-born people with similar demographic characteristics (particularly age and gender). It found that spending attributed to the foreign born on health and social care services was lower per person per year than for the UK born, while spending on education was higher. Expected spending per person for recent migrants was lower than for the foreign born on average.

- This study did not quantify the effects of migrants using services differently compared to the UK born – for example, if they require extra assistance because of language barriers. These effects are extremely difficult to quantify systematically.

The impacts of migration on public services may depend on the extent to which providers are willing and able to adjust to increases in demand. For example, local authorities and the national government undertake detailed planning exercises to ensure that there are sufficient school places available for the number of students.

By contrast, the stock of social housing has not grown with the rising population, but has fallen over time. As a result, migration may affect UK-born applicants’ access to social housing, even though foreign born people rely on this type of housing less than demographically similar UK born residents.

A recent study estimated that two thirds of the decline since 1992 in UK-born households’ probability of living in social housing is due to falling numbers of social housing units, while increased demand due to immigration and changes in allocation rules affecting immigrants explained the other third.

Impacts on public services are also likely to vary by region and local authority, although there is little evidence on this kind of variation.

Second, migrants contribute to the provision of public services in two main ways: by paying taxes that contribute to funding these services; and as workers involved in their provision.

- Studies on the ‘net fiscal impact’ of migration have generally found that, overall, the foreign born make national and local tax contributions that are roughly comparable to the cost of the services and benefits they receive.

- Some public services rely heavily on migrant workers. Foreign born people are overrepresented in social care and in the NHS medical workforce, for example. However, it is not possible to quantify the impacts of this workforce on the availability and cost of these services, because of the very large number of assumptions that would be required.

Finally, we cannot say with certainty what the impacts of migration on the quality of public services are. In education, for example, some local areas have significant numbers of students with English as an additional language (EAL).

The share of students who were ‘known or believed’ to have a first language other than English was 18% in state-funded primary pupils and 14% in secondary schools, according to the January 2013 School Census. In London, the shares were 47.5% at primary and 38.9% at secondary. However, having a higher share of EAL students does not appear to reduce student attainment, the main indicator of the quality of education.

Thanks to Jackline Wahba and Martin Ruhs for comments. This work has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation but the content is the responsibility of the authors and of Full Fact, and not of the Nuffield Foundation.